It’s All About the Stuff: Collections, Interfaces, Power, and People

Tim Sherratt

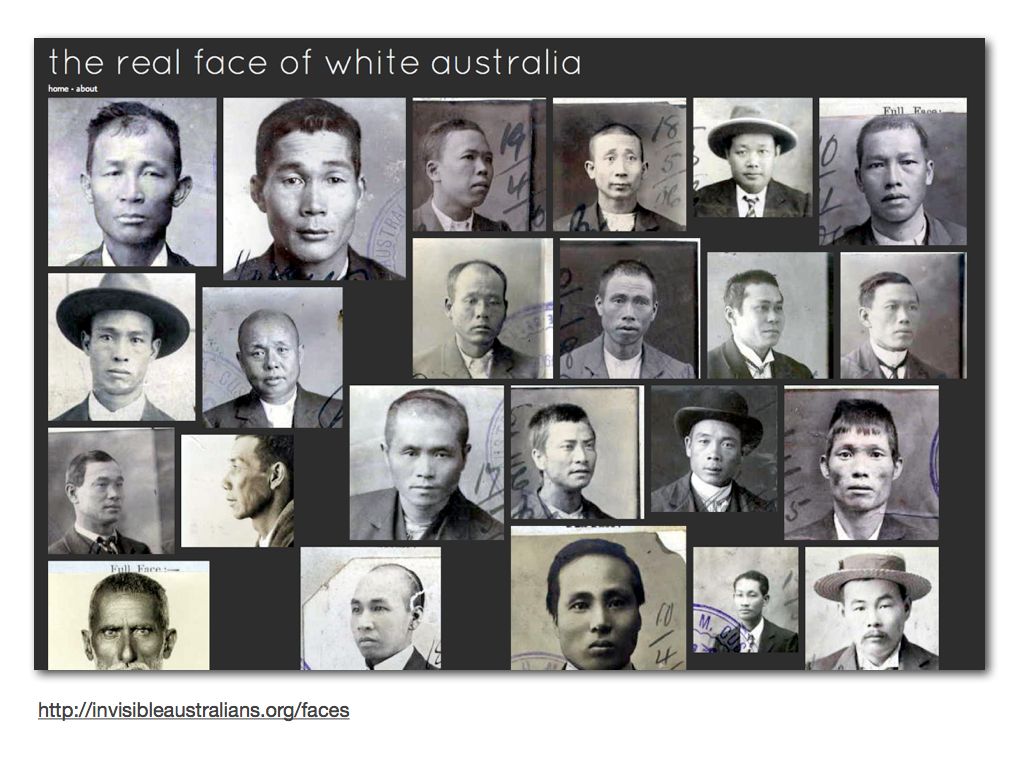

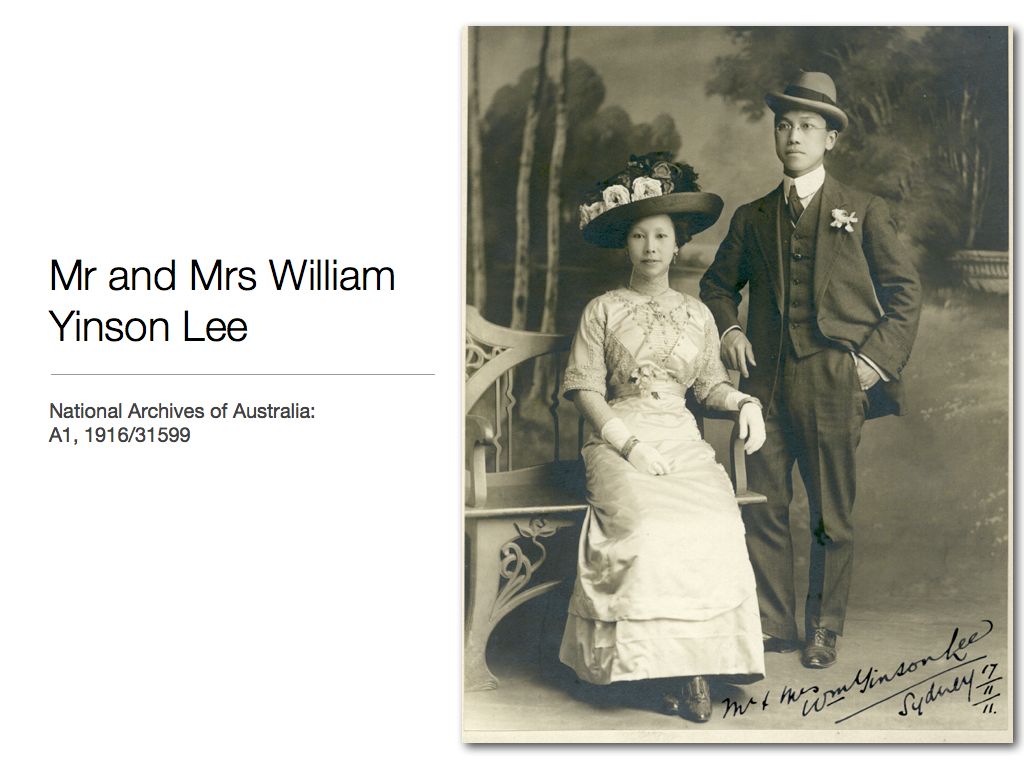

In 1901, one of the first acts of the Commonwealth of Australia was to create a system of exclusion and control designed to keep the newly-formed nation ‘white’. But White Australia was always a myth. As well as the Indigenous population, there were already many thousands of people classified as ‘non-white‘ living in Australia — most were Chinese, but there were also Japanese, Indians, Syrians and Indonesians.

Here are some of them…

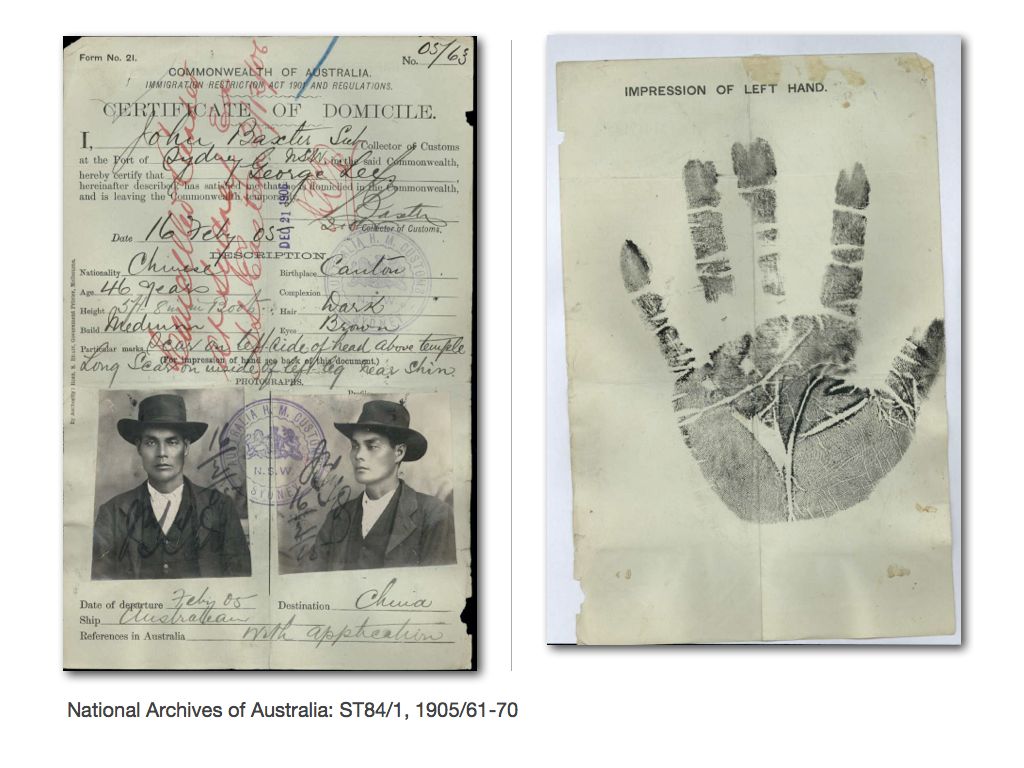

The administration of what became known as the White Australia Policy created a huge volume of records, much of which is still preserved within the National Archives of Australia. These photographs are attached to certificates that non-white residents needed to get back into the country if they decided to travel overseas. There are thousands upon thousands of these certificates in the Archives. Thousands of certificates representing thousands of lives — all monitored and controlled.

But is is too easy to see these people as the powerless victims of a repressive system. There were many acts of resistance. Some argued against the need to be identified ‘just like a criminal’. Others exercised control over their representation, submitting formal studio portraits instead of mug shots.

Most commonly and most powerfully, people resisted the policy simply by going ahead and living rich and productive lives.

My partner, Kate Bagnall, is helping to rewrite Australian-Chinese history by overthrowing the stereotype of the culturally isolated Chinese man living a lonely, meagre existence surrounded by gambling and opium dens. By mining the available records, by reading against the grain of contemporary reports, and by working with family historians, Kate is documenting their intimate lives—their wives, their lovers, their families and descendants—the sorts of relationships that sent a shudder through the edifice of White Australia. Power can be reclaimed in many subtle and subversive ways.

‘The real face of White Australia’ is an experiment. It uses facial detection to technology to find and extract the photographs from digital copies of the original certificates made available through the National Archives of Australia’s collection database. The photographs you see here come from just one series, ST84/1. There’s no API to the collection so I reverse-engineered the web interface to create a script that would harvest the item metadata and download copies of all the digitised images. There are 2,756 files in this series. On the day I harvested the metadata, 347 of those files had been digitised, comprising 12,502 images. It took a few hours, but I just ran my script and soon I had a copy of all of this in my local database.

Then came the exciting part. Using a facial detection script I found through Google and an open source computer vision library, I started experimenting with ways of extracting the photos. After a few tweaks I had something that worked pretty well, so I pointed my aging laptop at the 12,502 images and watched anxiously as the CPU temperature rose and rose. It took a few emergency cooling measures, but the laptop survived and I had a folder containing 11,170 cropped images. About a third of these weren’t actually faces, but it was easy to manually remove the false positives, leaving 7,247 photos.

These photos. These people.

With my database fully primed and loaded it was just a matter of creating a simple web interface using Django for the backend and Isotope (a jQuery plugin) at the front. Both are open source projects. All together, from idea to interface, it took a bit more than a weekend to create, and most of that was waiting for the harvesting and facial detection scripts to complete. It would be silly to say it was easy, but I would say that it wasn’t hard.

What we ended up with was a new way of seeing and understanding the records — not as the remnants of bureaucratic processes, but as windows onto the lives of people. All the faces are linked to copies of the original certificates and back to the collection database of the National Archives. So this is also a finding aid. A finding aid that brings the people to the front.

According to Margaret Hedstrom, the archival interface ‘is a site where power is negotiated and exercised’.[1] Whether in a reading room or online, finding aids or collection databases are ‘neither neutral nor transparent’, but the product of ‘conscious design decisions’. We would like to think that this interface gives some power back to the people within the records. Their photographs challenge us to do something, to think something, to feel something. We cannot escape their discomfiting gaze.

But this interface represents another subtle shift in power. We could create it without any explicit assistance or involvement by the National Archives itself. Simply by putting part of the collection online, they provided us with the opportunity to develop a resource that both extends and critiques the existing collection database. Interfaces to cultural heritage collections are no longer controlled solely by cultural heritage institutions.

It’s these two aspects of the power of interfaces that I want to focus on.

There is a growing number of examples where the records created by repressive or discriminatory regimes have, in Eric Ketelaar’s words, ‘become instruments of empowerment and liberation, salvation and freedom’.[2] Nazi records of assets confiscated during the Holocaust have been used to inform processes of restitution and reparation. Government records have helped members of Australia’s Stolen Generations trace family members. Descendants of inmates incarcerated by American colonial authorities in what was the world’s largest leprosy colony in the Philippines, have embraced the administrative record as an affirmation of their own heritage and survival.[3] Records can find new meanings. Power can be reclaimed.

Technology can help. Tim Hitchcock has described how something as simple as keyword searching can turn archives on their heads. Recordkeeping systems tend to reflect the structures and power relations of the organisations that create them. The ‘hierarchical and institutional nature of most archives’, Hitchcock argues, ‘contains an ideological component which is sucked in with every dust-filled breath’.[4] But digitisation and keyword searching free us from having to follow the well-worn paths of institutional power. We can find people and follow their lives against the flow of bureaucratic convenience. We can gain a wholly new perspective on the workings of society. ‘What changes’, Hitchcock asks, ‘when we examine the world through the collected fragments of knowledge that we can recover about a single person, reorganised as a biographical narrative, rather than as part of an archival system?’[5]

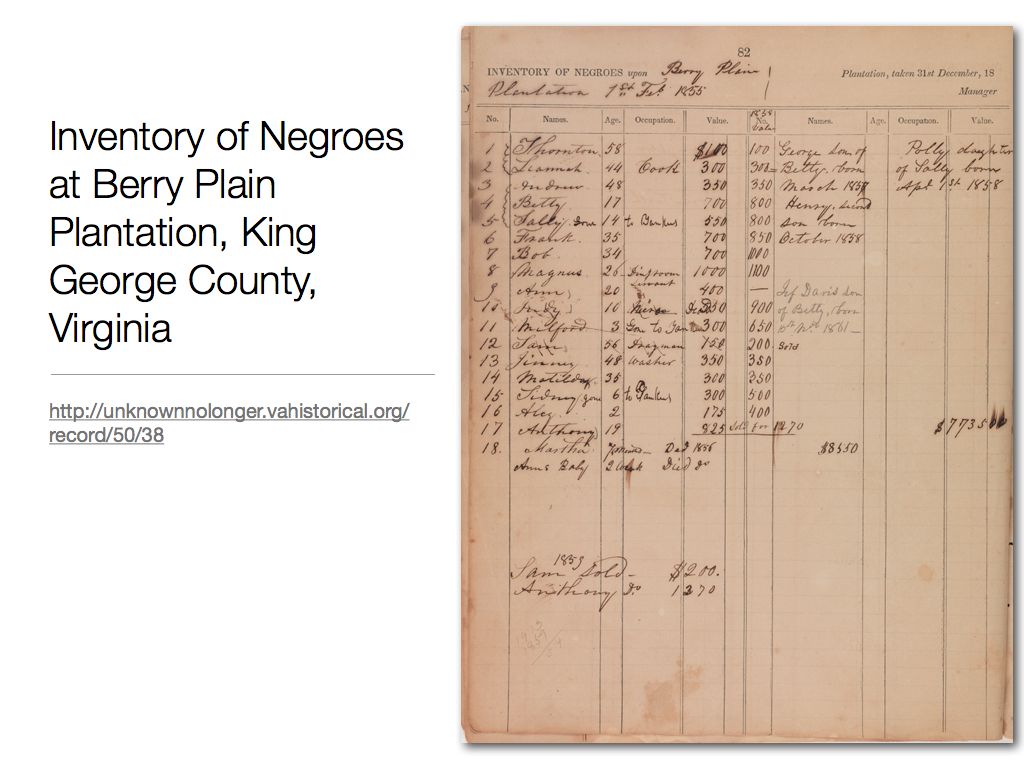

Projects such as Unknown no longer may help us answer that question.

It’s aiming to extract the names and biographical details of slaves from the 8 million manuscript documents held by the Virginia Historical Society. The documents include court records, receipts, wills and inventories. Here is a page from the ‘Inventory of Negroes at Berry Plain Plantation, King George County, Virginia’ for 1855, listing names, occupations and valuations.

Tim Hitchcock is one of the directors of London Lives a project that similarly seeks to find the people in 240,000 manuscript pages documenting the lives of plebeian Londoners in the 17th century.

More than three million names have already been extracted from the records of courts, workhouses, hospitals and other institutions. Work is continuing to link these names together, to merge these various shards of identity and piece together the experiences of London’s poorest inhabitants.

Remember me, from the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, is working with photographs taken by relief agencies in the aftermath of World War Two. The photographs are of displaced children who survived the Holocaust but were separated from families. What happened to them? The project is seeking public help to identify and trace the children.

These are all projects about finding people. They are projects about finding the oppressed, the vulnerable, the displaced, the marginalized and the poor and giving them their place in history. This is what Kate and I hope to do with Invisible Australians, the broader project of which our faces experiment is part.

‘Invisible Australians’ aims to extract more than just photographs. We want to record and aggregate the biographical data contained within the records of the White Australia Policy to extract the data and rebuild identities.

But we want to do more; we want to link these identities up with with other records, with the research of family and local historians, with cemetery registers and family trees, with newspaper articles and databases we don’t even know about yet. We want to find people, families, and communities.

It’s ridiculously ambitious and totally unfunded. But it is possible.

The most exciting part of online technology is the power it gives to people to pursue their passions. As with the faces, we don’t need the help of the National Archives. We need the records to be digitized, but that’s happening anyway and we can afford to be patient. Most of the tools we need already exist, and are free. In the past twelve months, for example, there have been a number of open source tools released for crowd-sourced transcription of manuscript records.

People with passions, people with dreams, people who are just annoyed and impatient, don’t have to wait for cultural institutions to create exactly what they need. They can take what’s on offer and change it.

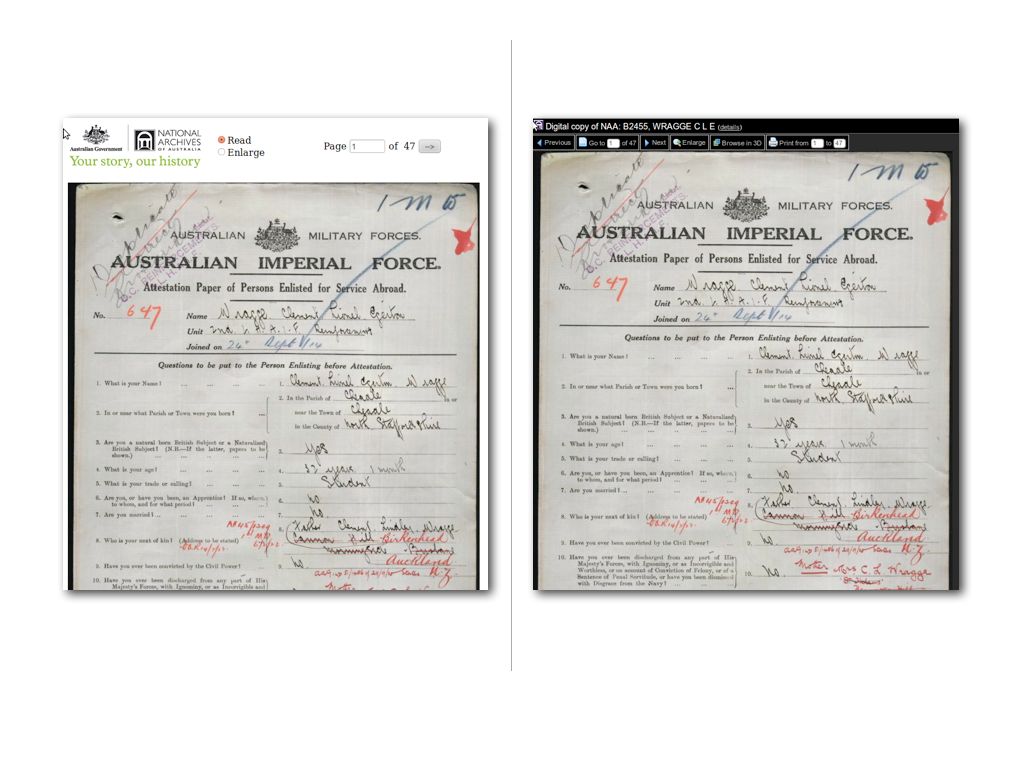

Interfaces can be modified. It is amazingly easy to write a script that will change the way a web page looks and behaves in your browser. I was frustrated by the standard interface to digitized files in the National Archives of Australia’s Recordsearch database—so I changed it.

Not only did make it look a bit nicer, I added new functions. My script lets you print a whole file or a range of pages and display the entire contents of the file on a pretty cool three-dimensional wall.

I’ve shared this script, and a few other Recordsearch enhancements. Anyone can install them with a click and use them.

Interfaces are sites of power, and we can claim some of that power for ourselves. Online technologies not only free us from the having to brave the physical intimidation of the reading room, they free us up to engage with the records in new ways. The archivist-on-duty would probably not be pleased if I pulled out some scissors and started snipping photos out of certificates. Or if I pulled a file apart and pasted its contents on the wall. But online we are free to experiment.

The power of cultural heritage organisations is perhaps expressed most forcefully in their ability to control the arrangement and description of their collections. ‘Every representation, every model of description, is biased’, note Verne Harris and Wendy Duff, ‘because it reflects a particular world-view and is constructed to meet specific purposes’.[6] Archives, libraries and museums are already starting to share this power, by allowing tagging, or seeking public assistance with description through crowd sourcing projects. But most of the these activities still happen within spaces created and curated by the institutions themselves. Our cathedrals of culture might be opening their doors and inviting the public to participate in their ceremonies, but that doesn’t make them bazaars. The architecture stills speaks of authority.

In any case, people already have a space where they can explore and enrich collections — it’s called the internet.

It would be great to see cultural institutions doing more to watch, understand and support what people are doing with collections in their own spaces — following them as they pursue their passions, rather than thinking of ways to motivate them.

A quick example… You might have heard of Zotero, it’s an open source project that lets you capture, annotate and organize your research materials.

One cool thing about Zotero is that you can build and contribute little screen scrapers, called translators, that let Zotero extract structured data from any old collection database. You might not be surprised to learn that I’ve created a translator for Recordsearch. Another cool thing about Zotero is that you can share the stuff that you collect in public groups.

Put those two cool things together and what do you have? Well to me they spell out user generated finding aids — parallel collection databases created by researchers simply pursuing their own passions.

Linked Open Data greatly increases opportunities for collection description to leak into the wider web. If objects and documents are identified with a unique URL, then anyone can can make and publish statements about them in machine-readable form. These statements can then be aggregated and explored. Initiatives such as the Open Annotation Collaboration will hasten the development of these shared descriptive and interpretative layers around our cultural collections.

And of course all this descriptive and interpretative work can be harvested back to enhance existing collection databases. We could start doing it now.

As well as exploring the possibilities of user-generated content, cultural institutions are starting to open up their collection data for re-use. APIs are great (though Linked Open Data is better), and New Zealand is lucky to have an organisation like DigitalNZ which just gets it. People can and will make cool things with your stuff.

But again, we don’t have to wait for everything to be delivered in a convenient, machine-readable form. If it’s on the web anybody can scrape, harvest and experiment.

You may know about the National Library of Australia’s newspaper digitisation project—it’s building a magnificent resource. But I wanted to do more than just find articles. I wanted to explore and analyze their content on a large scale. So I built a screen scraper to extract structured data from search results, and then used the scraper to power a series of tools. I have a harvester that lets you download an entire results set—hundreds or thousands of articles—with metadata neatly packaged for further analysis.

Or what about a script that graphs the occurrence of search terms over time, and allows you to ask questions like When did the Great War become the First World War?.

In the end I got a bit carried away and built my own public API to the Trove newspaper database.

I think it’s important to note that the tools I developed were guided by the types of questions I wanted to ask. While we should welcome APIs and celebrate their possibilities, we should also remain critical. APIs are interfaces, they too embed power relations. Every API has an argument. What questions do they let us ask? What questions do they prevent us from asking?

Even as we move into the rapidly-evolving realms of Linked Open Data, we have to constantly question the models we make of the world. Ontologies and vocabularies are culturally determined and historically specific. Yes, they too are interfaces, complete with their own distributions of power and authority. But we can revisit and change them. And we can relate our new models to our old models, capturing complex, long-term shifts in the way we think about the world. That’s incredibly exciting.

All of this hacking, harvesting, questioning, enriching and meaning-making makes me think about the possibilities of grassroots leadership. Online technologies enable people to take cultural institutions into unexpected realms. They can build their own interfaces, ask their own questions, determine their own needs — they can point the way instead of simply waiting to be served.

The idea of grassroots leadership brings me back to the title of this essay, ‘It’s all about the stuff’. It seems to me that we tend to model the interactions between cultural institutions and the public as transactions. The public are ‘clients’, ‘patrons’, ‘users’ or ‘visitors’. But the sorts of things I’ve been talking about today give us a chance to put the collections themselves squarely at the centre of our thoughts and actions. Instead of concentrating on the relationship between the institution and the public, we can can focus on the relationship we both have with the collections.

It’s all about the stuff.

It’s all about the respect and responsibility we both have for our collections.

It’s all about the respect and responsibility we both have for people like this.

This is a modified version of a paper I presented at the National Digital Forum, 30 November 2011.

- [1]Margaret Hedstrom, “Archives, Memory, and Interfaces with the Past,” Archival Science 2 (2002): 22.↩

- [2]Eric Ketelaar, “Archival Temples, Archival Prisons: Modes of Power and Protection,” Archival Science 2 (2002): 229.↩

- [3]Ricardo L Punzalan, “Archives and the Segregation of People with Leprosy in the Philippines,” presented at ICHORA-4, University of Western Australia, 2008, pp. 93-102.↩

- [4]Tim Hitchcock, “Digital Searching and the Re-formulation of Historical Knowledge,” in Mark Greengrass and Lorna Hughes (eds), The Virtual Representation of the Past (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2008), 87.↩

- [5]Tim Hitchcock, p.90.↩

- [6]Wendy M. Duff and Verne Harris, “Stories and Names: Archival Description as Narrating Records and Constructing Meanings,” Archival Science 2 (2002): 275. ↩