Topic Modeling: A Basic Introduction

Megan R. Brett

The purpose of this post is to help explain some of the basic concepts of topic modeling, introduce some topic modeling tools, and point out some other posts on topic modeling. The intended audience is historians, but it will hopefully prove useful to the general reader.

What is Topic Modeling?

Topic modeling is a form of text mining, a way of identifying patterns in a corpus. You take your corpus and run it through a tool which groups words across the corpus into ‘topics’. Miriam Posner has described topic modeling as “a method for finding and tracing clusters of words (called “topics” in shorthand) in large bodies of texts.”

What, then, is a topic? One definition offered on Twitter during a conference on topic modeling described a topic as “a recurring pattern of co-occurring words.” A topic modeling tool looks through a corpus for these clusters of words and groups them together by a process of similarity (more on that later). In a good topic model, the words in topic make sense, for example “navy, ship, captain” and “tobacco, farm, crops.”

How does it work?

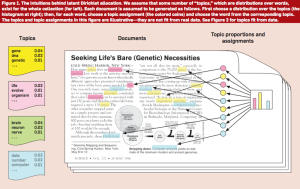

One way to think about how the process of topic modeling works is to imagine working through an article with a set of highlighters. As you read through the article, you use a different color for the key words of themes within the paper as you come across them. When you were done, you could copy out the words as grouped by the color you assigned them. That list of words is a topic, and each color represents a different topic. Note: this description is inspired by the following illustration from David Blei’s article [pdf], which is one of the best visual representations of a topic I’ve found.[1]

How the actual topic modeling programs is determined by mathematics. Many topic modeling articles include equations to explain the mathematics, but I personally cannot parse them. The best non-equation explanation of how at least one topic modeling program assigns words to topics was given by David Mimno at a conference on topic modeling held in November 2012 by the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Humanities. As he explains (starting at around 9:00), the computer compares the occurrence of topics within a document to how a word has been assigned in other documents to find the best match (you can find Mimno’s slides on his website).

The model Mimno is explaining is latent Dirichlet allocation, or LDA, which seems to be the most widely used model in the humanities. LDA has strengths and weaknesses, and it may not be right for all projects. It does form the basis of MALLET, which is an open source and fairly accessible tool for topic modeling.

For more detailed explanations of how topic modeling works, and how it can be applied, take a look at the other speaker videos from the MITH/NEH conference. Ted Underwood has offered his explanation of how the process works in a post titled Topic Modeling Made Just Simple Enough.

Scott B. Weingart has written an excellent overview of current scholarship on topic modeling with links to everything from a fable-like explanation of topic modeling to articles which delve into the technical side. Many of the more complex articles and posts include complex-looking equations, but it is possible to understand the basics of topic modeling without knowing how to unravel the equations.

What do you need to topic model?

1. A corpus, preferably a large one

If you wanted to topic model one fairly short document, you might be better off with a set of highlighters or a good pdf annotation tool. Topic modeling is built for large collections of texts. The people behind Paper Machines, a tool which allows you to topic model your Zotero library, recommend that you have at least 1,000 items in the library or collection you want to model. The question of “how big” or “how small” is ultimately subjective, but I think you want to have at least in the hundreds if not a minimum of 1,000 documents in your corpus. Bear in mind that you define what a document is for the tool. If you have a particularly long work you can divide it into pieces and call each piece a document.

With some tools, you will have to prepare the corpus before you can topic model. Essentially what you have to do is tokenize the text, changing it from human-readable sentences to a string of words by stripping out the punctuation and removing capitalization. You can also tell it to ignore “stopwords” which you define, which usually include things like a, the, and, etc. What you (hopefully) end up with is a document with no capitalization, punctuation, or numbers to throw off the algorithms.

There are a number of ways to clean up your text for topic modeling (and text mining). For example, you can use Python and Regular Expressions, the command line (Terminal), and R.

If you want to give topic modeling a try, but do not have a corpus of your own, there are sources for large data. You could, for example, download the complete works of Charles Dickens as a series of text files from Project Gutenberg, which makes a large number of public domain works available as txt files. JSTOR Data for Research, which requires registration, allows you to download the results of a search as a csv file, which is accessible for MALLET and other topic modeling and text mining processes.

2. Familiarity with the corpus

This may seem counterintuitive if you’re planning to use topic modeling to help you find out more about a large corpus, and yet it is very important that you at least have an idea of what should be there. Topic modeling is not an exact science by any means. The only way to know if your results are useful or wildly off the mark is to have a general idea of what you should be seeing. Most people would probably spot the outlier in a topic of “tobacco, farm, crops, navy” but more complex topics might be less obvious.

3. A tool to do the topic modeling

However you’re going to topic model, you need to decide what you are going to use and have a way to use it.

Many humanists use MALLET and by extension LDA. MALLET is particularly useful for those who are comfortable working in the command line, and it takes care of tokenizing and stopwords for you. The Programming Historian has a tutorial which walks you through the basics of working with MALLET.

The Stanford Natural Language Processing Group has created a visual interface for working with MALLET, the Stanford Topic Modeling Toolbox. If you chose to work with TMT, read Miriam Posner’s blog post on very basic strategies for interpreting results from the Topic Modeling Tool.

If you have a WordPress install and are comfortable with Python, check out Peter Organisciak’s post on processing WordPress exports for MALLET.

It is important to be aware that you need to train these tools. Topic modeling tools only return as many topics as you tell them to; it matters whether you specify 50, 5, or 500. If you imagine topic modeling as a switchboard, there are a large number of knobs and dials which can be adjusted. These have to be tuned, mostly through trial and error, before the results are useful.

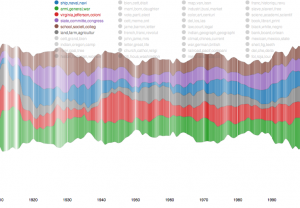

If you use Zotero, you can use Paper Machines to topic model particularly large collections. Paper Machines is an open-source project, the result of a collaboration between Jo Guldi and Chris Johnson-Roberson, supported by Google Summer of Code, the William F. Milton Fund, and metaLAB @ Harvard. You can do nifty visualizations with Paper Machines, but for topic modeling you need at least 1000 documents. Luckily, you can supplement your Zotero library with data from JSTOR Data for Research.

4. A way to understand your results

Topic modeling output is not entirely human readable. One way to understand what the program is telling you is through a visualization, but be sure that you know how to understand what the visualization is telling you. Topic modeling tools are fallible, and if the algorithm isn’t right, they can return some bizarre results.

Ben Schmidt, who is using k-means clustering to classify whaling voyages, plugged his data into LDA to demonstrate the ways in which modeling can return results which ultimately make no sense. His post explains the dangers of chimerical models, where two clusters get stuck together (think “cat, fish, mouse” and “gun, rod, hunt”).

Topic Modeling and History

Topic modeling is not necessarily useful as evidence but it makes an excellent tool for discovery.

Cameron Blevins has a series of posts on his work text mining and topic modeling the diary of Martha Ballard. He has compared his results to Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s work, which was done by hand, and the two result sets generally align. His work is particularly useful for understanding the potential and limitations of topic modeling, as so many historians are already familiar with the source material, having read Ulrich’s book A Midwife’s Tale.[2] Both Blevins and Ulrich had to be familiar with the content of the diary and its historical context in order to make sense of their findings. The results of the topic modeling help to uncover evidence already in the text.

Newspapers have proved to be a popular subject for topic modeling, as it provides a way to get at change over time from a daily source. David J. Newman, a computer scientists, and Sharon Block, a historian, worked together to topic model the Pennsylvania Gazette.[3] Table 4 in their article (pdf) lists off the most likely words in a topic and the label they assigned to that topic; some of the topics are obvious but others make it clear that you have to understand the context of a corpus in order to read the results. Another example of topic modeling a historic newspaper is a project from the University of Richmond (VA), Mining the Dispatch. The objective of the project was to explore social and political life in Richmond during the Civil War. The site allows you to interact with the topic models with some interpretation. Exploring this site might help you understand how modifying settings in a topic modeling tool changes the output.

Topic modeling is complicated and potentially messy but useful and even fun. The best way to understand how it works is to try it. Don’t be afraid to fail or to get bad results, because those will help you find the settings which give you good results. Plug in some data and see what happens.

Originally published by Megan R. Brett on December 12, 2012.

- [1]Blei, D. 2012. “Probabilistic Topic Models.” Communications of the ACM 55 (4): 77–84. doi: 10.1145/2133806.2133826 Available at http://www.cs.princeton.edu/~blei/papers/Blei2012.pdf.↩

- [2]Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, A Midwife’s Tale (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990).↩

- [3]David J. Newman and Sharon Block, “Probabilistic Topic Decomposition of an Eighteenth-Century American Newspaper” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 57(6):753-767, 2006. Available at http://www.ics.uci.edu/~newman/pubs/JASIST_Newman.pdf↩