Evaluating Collaborative Digital Scholarship (or, Where Credit is Due)

Bethany Nowviskie

This is the lightly edited text of a talk given at the 2011 NINES Summer Institute, a National Endowment for the Humanities-funded workshop on evaluating digital scholarship for purposes of tenure and promotion, hosted by the Networked Infrastructure for Nineteenth-Century Electronic Scholarship. It builds on a more formal essay written for an open-access cluster of articles on the topic in Profession, the journal of the Modern Language Association (MLA). A pre-print of that essay was provided to NINES attendees in advance of the Institute.

As you’ll divine from the image above, I’ll spend my time today addressing human factors: framing collaboration within our overall picture for the evaluation of digital scholarship. I’ll pull several of the examples I’ll share with you from my contribution to the Profession cluster that our workshop organizers made available, and my argument will be familiar to you from that piece as well. But I thought it might be useful to lay these problems out in a plain way, in person, near the beginning of our week together. Collaborative work is a major hallmark of digital humanities practice, and yet it seems to be glossed over, often enough, in conversations about tenure and promotion.

We can trace a good deal of that silence to a collective discomfort, which much of my recent (“service”) work has been designed to expose — discomfort with the way that our institutional policies, like those that govern ownership over intellectual property, codify status-based divisions among knowledge workers of different stripes in our colleges and universities. These issues divide digital humanities collaborators in even the healthiest of projects, and we’ll have time afterwards, I hope, to talk about them.

But I want to offer a different observation now, more specific to the process that scholars on tenure and promotion committees go through in assessing readiness for advancement among their acknowledged peers. My observation is that the tenure and promotion (T&P) process is a poor fit to good assessment (or even, really, to recognition) of collaborative work, because it has evolved to focus too much on a particular fiction. That fiction is one of “final outputs” in digital scholarship.

In 2006, the MLA’s task force on evaluating scholarship issued an important report. It asserts the value of collaboration even in an institutional situation where “solitary scholarship, the paradigm of one-author–one-work, is deeply embedded in the practices of humanities scholarship, including the processes of evaluation for tenure and promotion.”

That sets a kind of charge for us, and I’ll read the words of the task force to you:

Opportunities to collaborate should be welcomed rather than treated with suspicion because of traditional prejudices or the difficulty of assigning credit. After all, academic disciplines in the sciences and social sciences have worked out rigorous systems for evaluating articles with multiple authors and research projects with multiple collaborators. We need to devise a system of evaluation for collaborative work that is appropriate to research in the humanities and that resolves questions of credit in our discipline as in others. The guiding rule, once again, should be to evaluate the quality of the results. (“Report” 56–57)

I see this as a clear and unequivocal endorsement of the work for which the set of preconditions I’ll offer you in a little bit intends to clear ground. But I want to pick at that last sentence a little, and encourage some wariness about the teleological thrust of the phrase, “quality of results.”

The danger here (which many of you confirmed you see this happening) is that T&P committees faced with the work of a digital humanities scholar will instigate a search for print equivalencies — aiming to map every project that is presented to them, to some other completed, unary and generally privately-created object (like an article, an edition, or a monograph). That mapping would be hard enough in cases where it is actually appropriate — and this week we’ll be exploring ways to identify those and make it easier to draw parallels. But I am certain, if you look only for finished products and independent lines of responsibility, you will meet with frustration in examining the more interesting sorts of digital constructions. In examining, in other words, precisely the sort of innovative work you want to be presented with. To make a print-equivalency match-up attempt across the board, in every case, is to avoid a much harder activity, the activity I want to argue is actually the new responsibility of tenure and promotion committees. This is your responsibility to assess quality in digital humanities work — not in terms of product or output — but as embodied in an evolving and continuous series of transformative processes.

Many years ago, when we were devising an encoding scheme for a project familiar to NINES attendees, the Rossetti Archive, two of our primary sites for inquiry and knowledge representation were the production history and the reception history of the Victorian texts and images we were collecting and encoding. I find (as perhaps many of you do) that I still locate scholarly and artistic work along these two axes. In conversations about assessment, however, we are far too apt to lose that particular plot. This is because production and reception have been in some ways made new in new media (or at least a bit unfamiliar), and also because they’ve never been adequately embedded — again, as activities, not outcomes — in our institutional methods for quality control.

We have to start taking seriously the systems of production and of reception in which digital scholarly objects and networks are continuously made and remade. If we fail to do this, we’ll shortchange the work of faculty who experiment consciously with such fluidity — but worse: we will find ourselves in the dubious moral position of overlooking other people, including many non-tenure-track scholars, who make up those two systems.

Digital scholarship happens within complex networks of human production. In some cases, these networks are simply heightened versions of the relationships and codependencies which characterized the book-and-journal trade; and in some cases they are truly incommensurate with what came before. However you want to look at them, it’s plain that systems of digital production require close and meaningful human partnerships. These are partnerships that individual scholars forge with programmers, sysadmins, students and postdocs, creators and owners of content, designers, publishers, archivists, digital preservationists, and other cultural heritage professionals. In many cases, the institutional players have been there for a long time, but collaboration, now, has been made personal again (by virtue of the diversifying of skillsets) and is amplified in degree through the experimental nature of much digital humanities work. (This is an interesting observation to make, perhaps, about our scholarly machine in the digital age. Despite all the focus on cyberinfrastructure and scholarly workflows, we’re fashioning ever closer, more intimate and personalized systems of production.)

To offer just one small example: compare the amount of conversation about layout, typography, and jacket design a scholar typically has with the publisher of a printed book — to the level of collaborative work and intellectual partnership between a faculty member and a Web design professional who (if they’re both doing their jobs well) work together to embed and embody acts of scholarly interpretation in closely-crafted, pitch-perfect, and utterly unique online user experiences.

But it’s not just that we (we evaluators, we tenure committees) fail to appreciate collaboration on the production side. We neglect, too, to consider the systems of reception in which digital archives and interpretive works are situated. In many cases, the “products” of digital scholarship are continually re-factored, remade, and extended by what we call expert communities (sometimes reaching far beyond the academy) which help to generate them and take them up. Audiences become meaningful co-creators. And more: an understanding of reception now has to include the manner in which digital work can be placed simultaneously in multiple overlapping development and publication contexts. Sometimes, “perpetual beta” is the point! Digital scholarship is rarely if ever “singular” or “done,” and that complicates immensely our notions of responsibility and authorship and readiness for assessment.

So my contention is that the multivalent conditions in which we encounter and create digital work demonstrate just how much we are impoverishing our tenure and promotion conversations when we center them on objects that have been falsely divorced from their networks of cooperative production and reception. Now, okay: certainly, committees can and do confront situations in which individual scholars have created digital works without explicit assistance or with minimal collaborative action. But those have long been the edge cases of the digital humanities — so why should our evaluative practices assume that they’re the rule and not the exception?

There’s something deeper to this, though, and it has to do with the academy’s taking, collectively, what is in effect a closed-down and defensive stance toward the notion of authorship. As an impulse, it certainly stems to the larger feeling of embattlement in our corner of the academy. But we must ask ourselves: do we really want to assert the value and uniqueness of a scholar’s output by protecting an outmoded and often patently incorrect vision of the solitary author? Is that the best way to build and protect what we do, together? What kind of favor do we think we’re doing the humanities, when we stylize ourselves into insignificance in this particular way?

To get back to people, here’s my fear: that we’re driving junior scholars, who lack good models and are made conservative by complex anxieties, toward two poor options. These are 1) dishonesty to self, and 2) dishonesty toward others. In the first case, we are putting them in a position where they may choose to de-emphasize their own innovative but collaborative work because they fear it will not fit the preconceived notion of valid or significant scholarly contribution by a sole academic. That’s dishonesty to self. The even nastier flip side is the second case: causing them to elide, in the project descriptions they place in their portfolios, the instrumental role played by others — by technical partners and so-called “non-academic” co-creators.

Now, you might expect me to go straight for a mushy and obvious first step — to argue today that we should work to increase our appreciation for collaborative development practices in the digital humanities. It makes sense that fostering an appreciation — that clarifying what collaboration means in digital humanities — could lead to a formal recognition of the collective modes of authorship that digital work very often implies. Unfortunately, we have to roll things back a bit — and this is why I used the word “Preconditions” in the title of my Profession essay.

In too many cases (this is disheartening, but true) scholars and scholarly teams need reminders that they must negotiate the expression of shared credit at all — much less credit that is articulated in legible and regularized forms. By that I mean forms acceptable within the differing professions and communities of practice from which close collaborators on a digital humanities project may be drawn.

We evaluate digital scholarship through a bootstrapped chain of responsibilities. Professional societies and scholarly organizations set a tone. Institutional policy-making groups define the local rules of engagement. Tenure committees are plainly responsible for educating themselves (they often forget this) about the nature of collaborative work in the digital humanities, so that they may adequately counsel candidates and fairly assess them. Scholars who offer their work for evaluation are, in turn, responsible for making an honest presentation of their unique contributions and of the relationship they bear to the intellectual labor of others.

And digital humanities practitioners working outside the ranks of the tenured and tenure-track faculty have a role to play in these conversations as well. We’re talking here about people like me and many of my colleagues in the digital humanities world, like the people I imagine partner with you at your home institutions, and like some of the folks who built NINES and 18th-Connect. We are hybrid scholarly and technical professionals subject to alternate, but equally consequential (though often less protected) mechanisms of assessment. We need you, the tenured and tenure-track faculty, to support us when we assert that credit must be given where it is due. I’ll talk in a little bit about an event — also organized with National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) support — that took on exactly this issue, and how making such assertions might hasten the regularization of fair and productive evaluative practice among tenure-track and non-tenure-track digital humanities practitioners alike.

But I have to stop to acknowledge that people on my side of that fence (that is, humanities PhDs working as “alternative academics” off the straight and narrow path to tenure) can sometimes be seen rolling their eyes and wondering aloud why you guys remain so hung up on defining individual (rather than your collective) self-worth. I have observed a sotto voce countdown that often happens among experienced digital humanists at panels on digital work at more traditional humanities conferences: “Can we go ten whole minutes into the Q&A without eating these particular worms?” My suspicion is that many folks on the “alt-ac track” are where they are, not only because of a congenital lack of patience, but because they are temperamentally inclined to reject some concepts that other humanities scholars remain tangled up in. And one of the most invidious of these is a tacit notion of scholarly credit as a zero-sum game, which functions as an underlying inhibitor to generous sharing.

But let’s talk about this week. Wouldn’t it be brilliant if this group, with all the energy of NINES and the authority with which it has come to speak, and under the auspices of a prestigious NEH Institute — what if this group could offer, loudly, a primary motivator or two to counter the inhibiting notion that there’s only so much credit to go around? I’ll give you one.

Please consider that the report that comes from this NINES workshop should assert very clearly that healthier scholarship will result from generous and full acknowledgment of the contributions of collaborators — that this kind of acknowledgment must be made and respected in tenure and promotion cases — and that we should begin considering seriously (as the MLA’s task force suggested years ago) the highly legible and articulated modes of acknowledgment that are common in laboratory partnerships within the sciences.

Why do I say “healthier” scholarship will result? Take it from somebody who trained as a humanities scholar but has worked as a peer, for her entire career, with librarians, software developers and designers, professional society representatives, and digital publishers of various sorts. I am convinced that the mere listing of multiple collaborators contributes to what I’ll call the Three Essential P’s. Giving fair and even generous credit to your digital humanities collaborators from all quarters of the academy will make:

- imaginative production,

- enthusiastic promotion,

- and committed preservation

of digital humanities work a shared and personal enterprise. It’ll make your scholarly work an enterprise in which, in the most granular sense, named librarians, technologists, administrators, and researchers will feel a private as well as professional stake. You just do a better job, now and far into the future, with things that have your name on them.

Maybe part of the reason it is so hard to latch onto the issue of proper credit for diverse collaborators is that those collaborators are represented by so many different professional societies and advocacy groups. Let’s check in with just a few. I’ve found the most instructive examples in the field of public (which is often to say digital) history. My favorite is a statement issued by a “Working Group on Evaluating Public History Scholarship,” commissioned jointly by the American Historical Association (AHA), the National Council on Public History, and the Organization of American Historians (OAH). In 2010, they put out something called “Tenure, Promotion, and the Publicly Engaged Academic Historian” (PDF). This piece starts in same key I did today, on the matter of process. It strongly endorses the AHA’s Statement on Standards of Professional Conduct, which defines scholarship as “a process, not a product, an understanding [they say] now common in the profession.” And it goes on:

The scholarly work of public historians involves the advancement, integration, application, and transformation of knowledge. It differs from “traditional” historical research not in method or in rigor but in the venues in which it is presented and in the collaborative nature of its creation. Public history scholarship, like all good historical scholarship, is peer reviewed, but that review includes a broader and more diverse group of peers, many from outside traditional academic departments, working in museums, historic sites, and other sites of mediation between scholars and the public. (Working Group 2)

Similarly, here’s something from the MLA’s 1996 report, “Making Faculty Work Visible”:

As institutions develop their own means of assessment, they should consider the wide range of activities that require faculty members’ professional expertise. These would include, in addition to activities more traditionally recognized, inter- and cross-disciplinary projects, teaching that occurs outside the traditional classroom, acquisition of the knowledge and skills required by new information technologies, practical action as a context for analyzing and evaluating intellectual work, and activities that require collective and collaborative knowledge and the dissemination of learning to communities not only inside but also outside the academy. (Making 54; my emphasis).

I want you to see where I think both of these statements are trending. It’s an important new notion. As we expand our understanding of the kinds of work open to assessment, we also need to recognize that digital scholarly collaboration speaks a different brand of peer review. It’s a good start, don’t you think? — to assert the validity of “collective and collaborative” knowledge production and to acknowledge that review is beginning to include “a broader and more diverse group of peers.” But let’s go a little further.

(And this, I think, you won’t find in any formal statements by a professional society; it might be new to this conversation.) Digital humanities practitioners don’t often say, but we all know that collaborative work involves a kind of perpetual peer review. What I mean by that is the manner in which continual assessment — often of the most pragmatic kind, and stemming from diverse quarters — becomes a part of day-to-day scholarly practice in the digital humanities. You don’t get this quite so clearly and regularly, in my experience, in any other kind of scholarly work. And it boils down to something simple. Every collaborative action in the development of a digital project asks one big question: Does it work?

Does it work? That is, can this certain theory or intellectual stance, combined with these particular modes of gathering, interpreting, and designing information, result in ongoing production of a reasonably functional and effective digital instantiation, or user experience, or implementation of a collection or a tool? In other words, peer review, in the digital humanities, is not a post-mortem. Instead, evolving intellectual models and digital content undergo constant review by collaborators who are trying to make everything work together. This is less a review of product, than of process itself. By implementing aligned systems or project components that make special demands of those models and resources, they are constantly assisting in the refinement of them. If, in a collaborative project, your code runs and is reasonably usable, and (more importantly) it makes sense in terms of the scholarly argument you and your collaborators are jointly building — then it has gone through some highly significant layers of systematic quality control already. You just can’t say the same of a single-author scholarly essay, even if you discussed a draft with students or peers. So that’s the pragmatic side of things.

Let’s return to the ethical. This is a dimension that also takes on special significance in the digital humanities. One option always before us, in thinking about collaborative relationships, is to default to a familiar binary: the division between authors and their publication service providers, including book designers and copyeditors, on the model of the university or commercial press. Here, we sometimes (slightly obnoxiously) congratulate ourselves on the way that hands-on work in digital scholarship helps us arrive at a deeper appreciation of technologies of text and media production. As Purdy and Walker note in their article in last year’s Profession:

Though authorial choices [in design modalities, technologies, and conventions] have traditionally been more limited in print, recognizing how collaboration allows for more informed decisions and production competencies can make us appreciate more its value in print as well as digital forms. (Purdy and Walker 186; my emphasis)

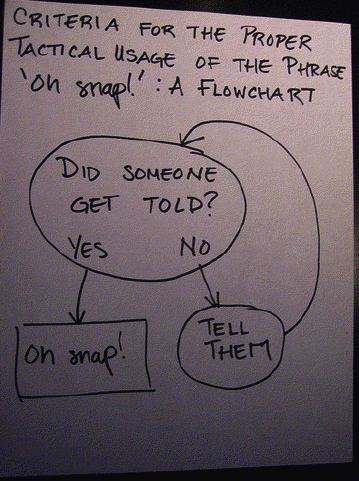

Fair enough. But I want to point out that there’s a weird and unsavory assumption, embedded in this passage, of the single scholar as authorial decision-maker. The digital humanities resist that. And I want to remind you workshop participants, that you should, as you’re writing recommendations this week, take pains to avoid implying that collaboration in digital humanities is merely a means of enhancing a privileged faculty member’s ability to make informed decisions or more sophisticated authorial and directorial choices. (Oh, as the flowchart reads, snap.) There will always be a temptation to trend that way in tenure and promotion conversations, because the stakes are so high and (as Joseph Harris gets at in this passage from his rhet-comp article, “Meet the New Boss, Same as the Old Boss) every structure we have reifies the notion of the solitary academic’s agency and individual achievement.

Almost all the routine forms of marking an academic career — CVs, annual faculty activity reports, tenure and promotion reviews — militate against [collaboration] by singling out for merit only… moments of individual ‘productivity.’ . . . The structures of academic professionalism, that is, encourage us not to identify with our coworkers but to strive to distinguish ourselves from one another — and, in doing so, to short-circuit attempts to form a sense of our collective interests and identity. (Harris 51–52)

All this is why (although as an organization, it may have a way to go) I like the way the AHA puts things. In its primary document on standards of conduct for historians, it encourages AHA constituents to be “explicit, thorough, and generous in acknowledging… intellectual debts” and promotes what it calls “vigilant self-criticism,” reminding them that “throughout our lives none of us can cease to question the claims to originality that our work makes and the sort of credit it grants to others.” I went looking, by the way, for something similar on ethics from MLA and could only find a narrower and more operational view: “a scholar who borrows from the works and ideas of other, including those of students, should acknowledge the debt, whether or not the sources are published. Unpublished scholarly material — which may be encountered when it is read aloud, circulated in manuscript, or discussed — is especially vulnerable to unacknowledged appropriation, since the lack of a printed text makes originality hard to establish.” (Statement of Professional Ethics)

Now, this is a statement deeply embedded not only in print culture but in a view of scholarship as the product of solitary, reflective action — something generated by an author, perhaps after discussion. And, you know, it’s not untrue of most of the scholarly work the MLA must address. But the AHA’s encouraging of ceaseless self-questioning and “explicit, thorough, and generous” acknowledgment seems better designed to promote the healthy collaborative relationships that digital scholarship demands. Anyway, it quickens the heart a little more.

Lest I give the impression that I’ve been cracking on the MLA too hard, allow me to scold the professional society nearest to my heart, and for which I take responsibility as an elected officer. The Association for Computers and the Humanities (ACH) is the professional organization perhaps best positioned to understand and articulate issues of collaboration and collaborative credit in digital humanities, and we have been conspicuously and entirely silent. This is beginning to change, but we’re not the only quiet ones. Professional societies across the disciplines have failed, far and wide, to advise scholars and tenure committees to value a risky and potentially transformative action. That action, I see now, is one of clarifying the difference — rather than the scholarly sameness — of public and digital humanities. (Timidity among digital humanities associations stems from decades of disenfranchisement, of making the argument that we are scholarly, too. If we take take advantage of our newfound centrality in only one way, perhaps this should be it.) Perhaps we could all begin do this is by emphasizing, rather than eliding, the degree to which digital scholars function within heterogenous collaborative networks — new networks (and I’m back to this again) of production and reception.

But we also need to make some concrete and pragmatic recommendations.

The MLA advocates one very specific model in its “Advice for Authors, Reviewers, Publishers, and Editors of Literary Scholarship.” Let’s take a moment to look at it.

Only persons who have made significant contributions and who share responsibility and accountability should be listed as coauthors of a publication. Other contributors should be acknowledged in a footnote or mentioned in an acknowledgments section. The author submitting the manuscript for publication should seek from each coauthor approval of the final draft. The following standards are usually applied to coauthored works: when names of coauthors are listed alphabetically, they are considered to be equal contributors; if out of alphabetical order, then the first person listed is considered the lead author. Coauthors should explain their role or describe their contribution in the publication itself or when they submit the publication for evaluation.

Can the expression of shared credit be so stark, easy, and uniformly applied as this recommendation suggests? I have questions and concerns. How might “responsibility and accountability” be apportioned in contexts where some collaborators provide content, others a digital and intellectual infrastructure for analysis or for publication, and still others are providing design expertise for digital presentation? All of these are part and parcel of a scholarly argument embodied in a digital project. All of these require thought, expertise, and conversation as part of a team. So maybe we should be looking for models in places where teamwork is more a norm. What about scientific publishing? Scholarly editing? Or maybe the most promising: R&D collectives in architecture and the arts?

Apportionment and expression of credit will never be simple or formulaic in digital humanities scholarship, because of the multiple communities and community norms which must be respected and engaged in any collaborative project. The best example I know in the digital humanities is INKE — the huge, multi-national, and interdisciplinary project on Implementing New Knowledge Environments in the context of the digital transformations of the book. I spend some time describing INKE and its governing documents in the Profession piece, so I won’t do that very closely now, but I want to encourage you to take a look at it. This group is notable in the digital humanities community for being self-reflective and regularly conducting analyses of its own processes of collaboration and project management. I think of INKE as a laboratory for measuring the effectiveness of mechanisms like project charters in large and heterogenous groups. Our Praxis Program in the Scholars’ Lab has taken a page from INKE in teaching the drafting of charters for collaborative work.

The basic idea of the INKE charter was to negotiate thorny issues of credit, authorship, and intellectual property in advance — and to have a way to bring new partners into an ongoing project in a way that gave them a sense of the group’s culture and ethos. The decisions about authorship and collective credit that INKE lighted on clearly have much in common with the lab model of the sciences.

According to the charter, collaborators

receive named co-authorship credit on presentations and publications that make direct use of research in which they took an active, as opposed to passive, role (i.e. research to which the individual made a unique and discernible contribution with a substantial effect on the knowledge generated); otherwise, [they] receive indirect credit via the INKE corporate authorship convention. (15–16)

This “corporate authorship convention” is a neat thing. Beyond the noticeable fact that INKE papers often have more listed authors than is common to see in the humanities, you’ll often observe “and INKE Research Group” as a formal listing in the byline of articles and conference presentations. Basically, when the INKE project itself is the topic of a presentation the charter specifies that “all team members should be co-authors.” Here are some more specifics:

We will adopt the convention of listing the team itself, so that typically the third or fourth author will be listed as INKE Research Group, while the actual named authors will be those most responsible for the paper. The individual names of members of the INKE Research Group should be listed in a footnote, or where that isn’t possible, through a link to a web page. Any member can elect at any time not to be listed, but may not veto publication. For presentations or papers that spin off from this work, only those members directly involved need to be listed as co-authors. The others should be mentioned if possible in the acknowledgments, credits, or article citations. (15–16)

The INKE group is quick to assert that the symbolic dimension of its crediting guidelines and charter is key to the success of the project, that it “signals the nature of [the INKE] working relationship.” They call it “a visible manifestation” of agreed-upon relationships, writing that “any published work and data represent the collaboration of the whole team, past and present, not the work of any sole researcher” (6–7). Clearly, they haven’t solved the problem of shared credit in digital humanities, but what’s important is that they have offered a documented and specific model which, over time, could be assessed for its effectiveness and for its impact both on the work that’s being done and on the careers of the people working — many of whom include postdoctoral researchers.

Of course, you don’t write a project charter or a statement of professional ethics unless you’re worried about something. Strong tensions underlie all of these things I’ve highlighted. Many seem to stem not from uncertainty about digital humanists’ ability to negotiate interpersonal relationships, but from a recognition that our institutional policies (listen up, attending deans and provosts!) codify inequities among collaborators of differing employment status. These are university policies that govern position descriptions, the awarding of research time or sabbaticals, standards for annual review, the definition of intellectual labor vs. mere “work for hire,” and (crucially) the ability of staff to assert ownership over their own intellectual property, including for purposes of releasing it as open access content or open source code.

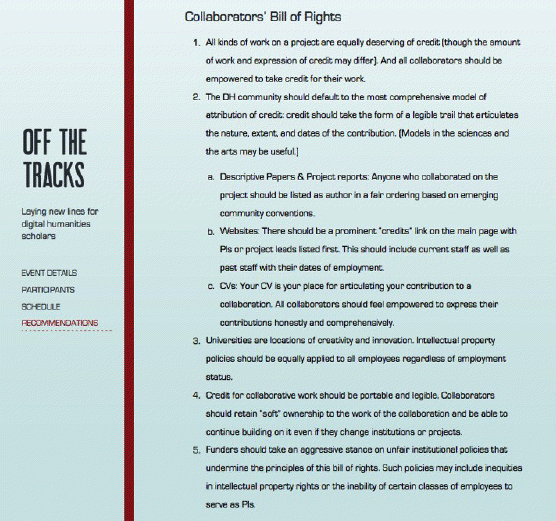

These were the concerns driving an NEH-funded workshop called “Off the Tracks: Laying New Lines for Digital Humanities Scholars,” which was held earlier this year. The workshop focused on administrative issues relating to equitable treatment and professionalization of “scholar-programmers” and “alternate academics” — those employees most likely to claim shared credit alongside faculty partners in digital research.

I was on a working group asked to look at issues of scholarly collaboration — together with Matt Kirschenbaum, Doug Reside, and Tom Scheinfeldt, and we drew on our experience administering MITH, the Scholars’ Lab, and the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media — three centers that are sites for a great deal of collaboration among people who may have similar backgrounds as scholars and technologists, but whose formal institutional status may vary a great deal. We drafted something we called a “Collaborators’ Bill of Rights,” which was later endorsed by the full workshop assembly and posted for public comment.

Basically, it’s an appeal for fair, honest, legible, portable (this is important!), and prominently-displayed crediting mechanisms. It also offers a dense expression of underlying requirements for healthy collaboration and adequate assessment from the point of view of practicing digital humanists, with special attention to the vulnerabilities of early-career scholars and staff or non-tenure-track faculty. I think things like this, and the INKE charter, are good demonstrations that the digital humanities community is increasingly prepared to address fundamental matters of collaborative credit leading to fair and accurate assessment of digital scholarship. This is going to happen at the grassroots level, and in ways that make sense to practicing digital humanists.

But your task is otherwise. Your audience is different.

What is going to resonate in our academic departments and among our disciplinary professional societies? What might we think of as the chief preconditions for the evaluation of collaborative digital humanities scholarship? I’ll give you six — maybe something to critique, or something to get you started:

- Committees must consider not only the products of digital work but the processes by which the work was (and perhaps continues to be) co-created;

- Scholars (even while they ask to have their critical agency as individuals taken seriously in tenure and promotion cases) are obligated to make the most generous and inclusive statements possible about the contributions of others;

- Credit should be expressed richly and descriptively, but also in increasingly standardized forms, legible within a variety of disciplines and communities of practice;

- We must negotiate expressions of shared credit at the outset of projects and continually, as projects evolve;

- We must promote fair institutional policies and practices in support of shared assertion of credit, such as those which make collective and individual ownership over intellectual property meaningful and actionable;

- And, finally, we must accept that collaborators themselves, regardless of rank or status, have the ultimate authority and responsibility for expressing their contributions and the nature of their roles.

So here are six possible preconditions. But really, underlying them all and maybe the most important thing you could clarify coming out of the NINES Institute, is that faculty under evaluation for promotion or tenure on the basis of collaborative digital projects must never be penalized for offering a full and fair catalog of contributions made by others — that it’s not a zero-sum game.

If the recommendations of this Institute can promote that understanding, and get picked up in the drafting of local, institutional policies, you’ll not only be enabling acts of intellectual generosity. I think you’re going to do something truly strategically productive for our disciplines. Formal and regular acknowledgment of collaboration as part of the ritual of assessment and faculty self-governance will have an educative function in the humanities, and it’ll be deeply consequential for policy and praxis within allied information and knowledge professions, like cultural heritage, IT, and libraries. I think we could expect it to lead to strengthened research-and-development partnerships in the digital humanities — and you’ve already heard me say that I think (back to our 3 P’s) that promoting a sense of shared ownership of knowledge production will result in better design decisions and more enthusiastic preservation of our cultural and scholarly record.

We’ve also got to keep fluid production, publication, and reception venues in the digital humanities in mind, and understand that new media offer important opportunities for scholars to engage not only new audiences but new peers, who will help to make and remake our digital scholarship in the years to come. By accepting any set of “preconditions,” we’re acknowledging that a great deal of work remains to be done, both by our professional societies in making recommendations and setting standards, and on the local scene in which individual scholars and committees of faculty peers continually enact our shared values.

There’s no reason to be afraid of a bit of work. And I think the loveliest thing about this Institute, in terms of the problem of evaluating collaborative digital scholarship, is that you’ve signed on to address the issue not just intensively, over the next few days, but collaboratively. I’ll be watching to see how you’re all credited on the final report!

Originally published by Bethany Nowviskie on May 31, 2011.

Works Cited

Advice for Authors, Reviewers, Publishers, and Editors of Literary Scholarship. Modern Language Association. MLA, 2007–08. Web. 6 July 2011.

Bhopal, Raj, et al. “The Vexed Question of Authorship: Views of Researchers in a British Medical Faculty.” British Medical Journal 314 (1997): 1009–12. Print.

“Collaborators’ Bill of Rights.” Off the Tracks: Laying New Lines for Digital Humanities Scholars. Maryland Inst. for Technology in the Humanities, U of Maryland. 21 Jan. 2011. Web. 5 July 2011.

Ede, Lisa, and Andrea A. Lunsford. “Collaboration and Concepts of Authorship.” PMLA 116.2 (2001): 354–69. Print.

Guidelines for Evaluating Work with Digital Media in the Modern Languages. Modern Language Association. MLA, 2000. Web. 19 Feb. 2011.

Harris, Joseph. “Meet the New Boss, Same as the Old Boss: Class Consciousness in Composition.” College Composition and Communication 52 (2000): 43–68. Print.

Hill, Timothy. “Modes of Collaboration in the (Digital) Humanities.” Digital Humanities—Works in Progress. Centre for Computing in the Humanities, King’s Coll. London, 28 Dec. 2010. Web. 19 Feb. 2011. Blog.

Kent, Phillip G., and Jenny Ellis. The Emerging Role of Scholar-Practitioner: Response to the Draft “Work Focus Categorisation Policy.” U of Melbourne Lib., 28 Jan. 2011. Web. 19 Feb. 2011.

Klenk, Nicole L., et al. “Evaluating the Social Capital Accrued in Large Research Networks: The Case of the Sustainable Forest Management Network, 1995–2009.” Social Studies of Science 40.6 (2010): 931–60. Print.

Liao, Chien Hsiang. “How to Improve Research Quality? Examining the Impacts of Collaboration Intensity and Member Diversity in Collaboration Networks.” Scientometrics 86.3 (2011): 1–15. Print.

Making Faculty Work Visible: Reinterpreting Professional Service, Teaching, and Research in the Fields of Language and Literature: Report of the MLA Commission on Professional Service. Modern Language Association. MLA, 12 Nov. 2003. Web. 5 July 2011.

McGann, Jerome. Imagining What You Don’t Know: The Theoretical Goals of the Rossetti Archive. 1997. Inst. for Advanced Technology in the Humanities, U of Virginia, 14 July 2010. Web. 19 Feb. 2011.

Nowviskie, Bethany. “Monopolies of Invention: Collaboration across Class Lines in the Digital Humanities.” 6 Dec. 2010. VeRSI. VeRSI, n.d. Web. 5 July 2011. Video of conf. address.

Purdy, James P., and Joyce R. Walker. “Valuing Digital Scholarship: Exploring the Changing Realities of Intellectual Work.” Profession (2010): 177–95. Print.

“Report of the MLA Task Force on Evaluating Scholarship for Tenure and Promotion.” Profession (2007): 9–71. Print.

Rosenblum, Brian, et al. “Readings on or Models of Collaboration in DH Projects?” Digital Humanities Questions and Answers. Assn. for Computers and the Humanities, Dec. 2010. Web. 19 Feb. 2011. Forum.

Ruecker, Stan, and Milena Radzikowska. “The Iterative Design of a Project Charter for Interdisciplinary Research.” Proceedings of the Seventh ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems DIS 08 (2008): 288–94. Web. 19 Feb. 2011.

Scheinfeldt, Tom. “Why Digital Humanities Is ‘Nice.’” Found History. Scheinfeldt, 26 May 2010. Web. 19 Feb. 2011. Blog.

Sheikh, Aziz. “Publication Ethics and the Research Assessment Exercise: Reflections on the Troubled Question of Authorship.” Journal of Medical Ethics 26 (2000): 422–26. Print.

Siemens, Lynne, and INKE Research Group. “From Writing the Grant to Working the Grant: An Exploration of Processes and Procedures in Transition.” New Knowledge Environments 1 (2009): 1–33. Web. 19 Feb. 2011.

Spiro, Lisa. “Collaborative Authorship in the Humanities.” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities. Spiro, 21 Apr. 2009. Web. 19 Feb. 2011. Blog.

———. “Examples of Collaborative Digital Humanities Projects.” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities. Spiro, 1 June 2009. Web. 19 Feb. 2011. Blog.

Statement of Professional Ethics. Modern Language Association. MLA, 16 Aug. 2005. Web. 5 July 2011.

Statement on Standards of Professional Conduct. Amer. Historical Assn., 8 June 2011. Web. 5 July 2011.

Woodward, Kathleen. “The Future of the Humanities—in the Present and in Public.” Dædalus 138.1 (2009): 110–23. Print.

Working Group on Evaluating Public History Scholarship. Tenure, Promotion, and the Publicly Engaged Academic Historian. Natl. Council on Public History, 5 June 2010.