Review of WordSeer, produced by Aditi Muralidharan, Marti Hearst, and Bryan Wagner

Amy Earhart

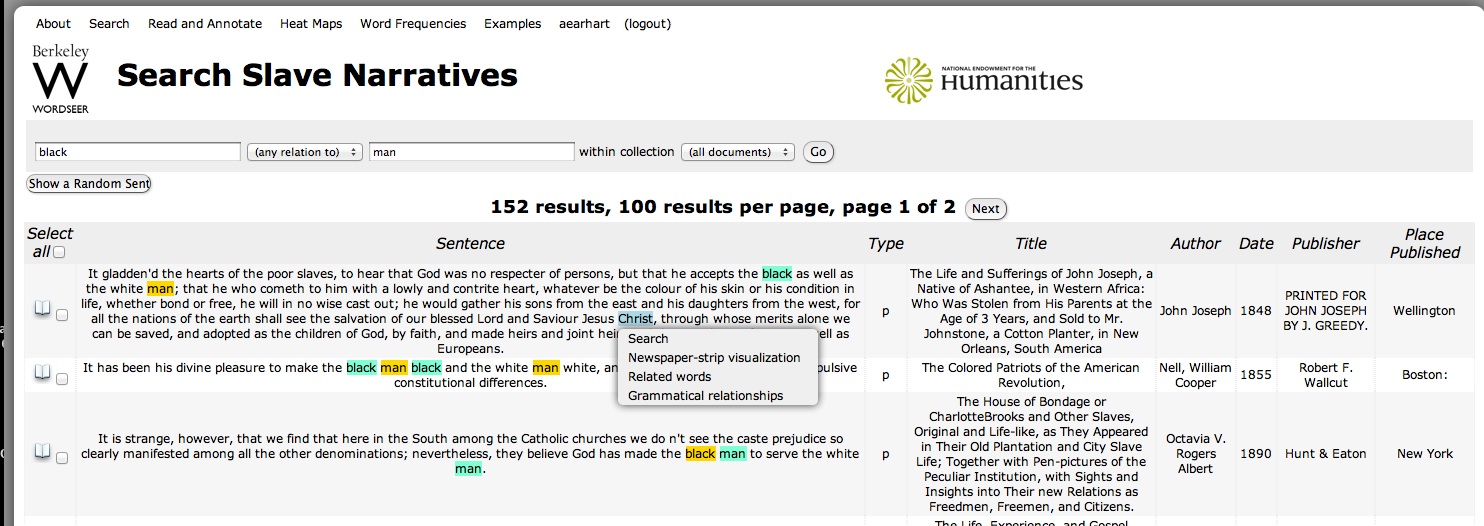

The WordSeer tool, developed at the University of California, Berkley by Aditi Muralidharan and Marti Hearst with research partner Bryan Wagner, is an exploratory analysis or “sensemaking” environment for literary texts. The tool is based on an understanding of literary analysis as a cyclical, rather than a linear, process, a notion that has been underemphasized in tool development where visualizations and datamining have generally been seen as exposing the text for scholarly treatment. WordSeer allows you to read a text, search for relationships between words and phrases, examine grammatical relationships, and examine produced heat map and tree visualizations.

WordSeer is the only tool specifically designed for literary analysis that will perform grammatical searches using natural language processing, a crucial step forward in literary tool approaches. The code is open and the developers encourage others to reuse and modify as needed. The tool accepts XML texts only, a reasonable choice given the prevalence of TEI/XML texts in digital literary scholarship though it would be nice to have the option of utilizing .txt files as well.

WordSeer is still in its infancy, so some issues should be resolved as it develops. Documentation has not yet been written, leaving the user to relying on experimentation for use. Several functions, including example searches and date selections, do not work consistently. In addition, the current version of WordSeer runs on only three sets of texts: The Slave Narratives from Documenting the American South, Shakespeare, and Stephen Crane. The Federal Writers Project Slave Interviews is listed as a test set, but not yet available. The developers have plans to open the tool for general use in 2013.

While the tool is limited at this stage of production it shows great promise. Grammatical searches using natural language processing promise a greater flexibility for scholars interested in moving from the macro to micro level of analysis. One of the most useful features of the tool is the ability to modify results of searches from the word or phrase level, allowing the scholar to start with distance reading and, based on results, drill down in to the materials for greater analysis.

In this respect the tool fulfills its claim to create a cyclical environment for scholarly exploration. One concern with grammatical structure approaches is the way in which the algorithm handles non-regularized grammatically structured texts. The test set of slave narratives, for example, may produce uneven results because of the multiple grammatical rules apparent in various dialects. In addition, the ability to locate grammatical relationships often throws an error, noting that the “sentence was too long to analyze.”

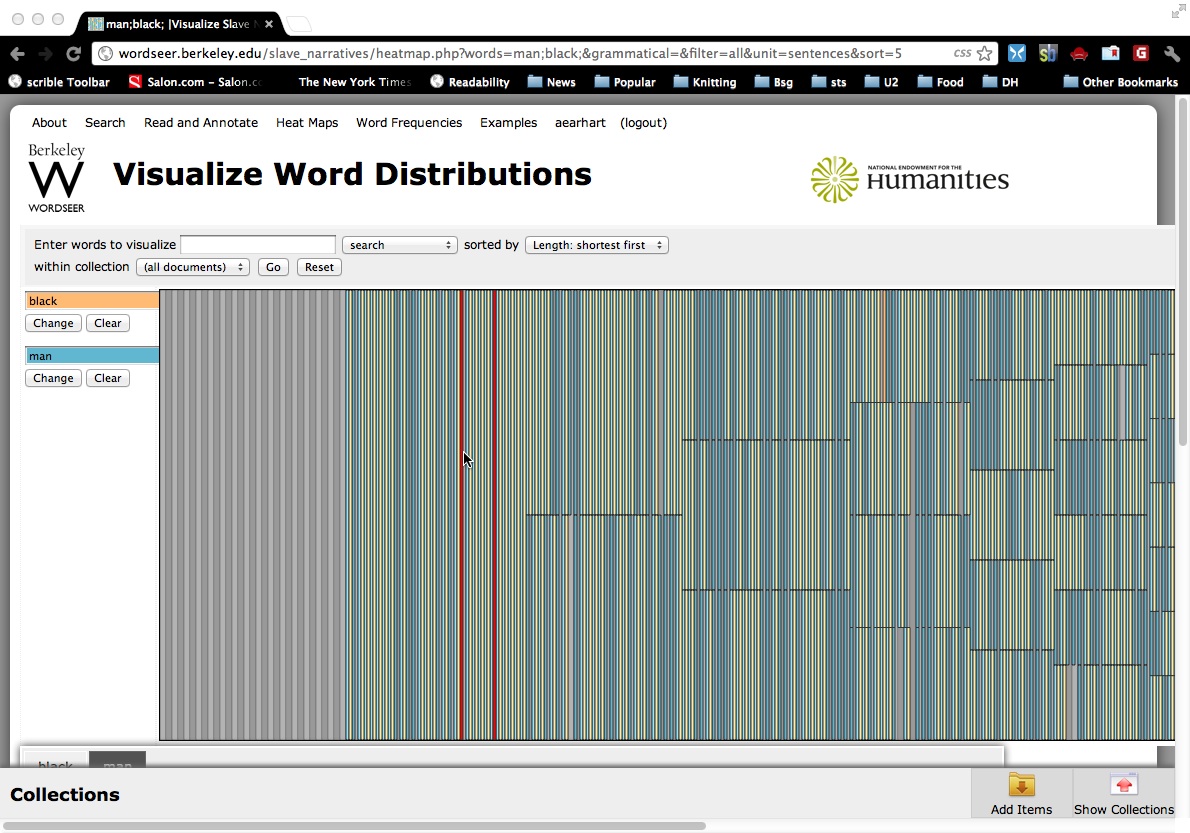

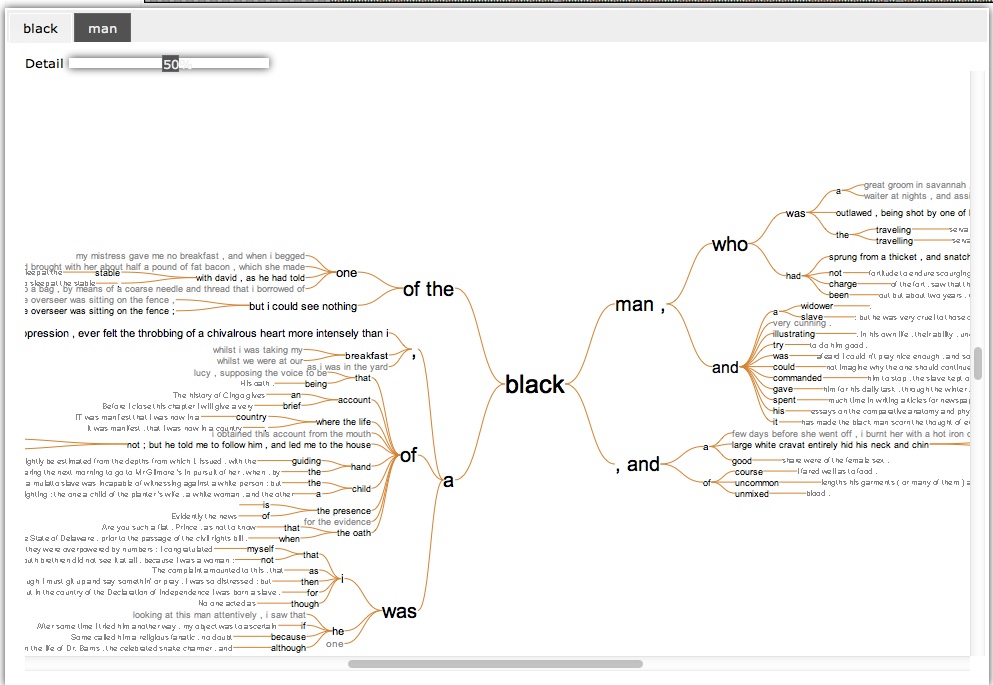

The visualizations deserve special mention. Searches produce both a newspaper strip and tree visualization of the frequency and relationships of words.

Both visualizations allow the user to easily locate the context of the word and to modify the search. The newspaper strip visualizations appear to be more difficult to interpret, and additional documentation on their use will be necessary. The trees, however, provide immediately recognizable results.

The only flaw that is apparent at this stage of the tool development is the choice of datasets for testing. Two of the three datasets, the Shakespeare and Crane materials, have no identified provenance, leaving one to question the reliability of results. The slave narratives materials are also problematic. The team tested the narratives to see if Richard Olney’s 1984 claim autobiographical slave narrative tropes proved correct.[1] The test set does demonstrate the strength of grammatical searches, since Olney claimed tropes like a cruel master or white paternity were common across texts, searches that would be nearly impossible with keyword approaches. However, the data set used for the test is flawed as the narratives, claimed to be autobiographical by their editors, are actually a mixed bag of fictional and non-fictional, black authored and white authored, autobiographical and biographical narratives.

Given the textual diversity, it is impossible to prove or disprove Olney’s criteria, which is premised on the black-authored autobiography. The same misunderstanding of the dataset is apparent with the decision to split selection for time periods at 1838. 1838 is the year slavery was abolished in the UK, but this set of data is focused on North America. I would encourage the WordSeer team to develop stronger ties to literary scholars who are able to move between technology and literary scholarship to develop more robust literary questions for analysis.

Regardless of such concerns, the tool offers great promise, and I await the open release in 2013.

- [1]Richard Olney, “I Was Born”: Slave Narratives, Their Status as Autobiography and as Literature,” Callaloo, 20 (Winter 1984): 46-73.↩