Where Material Book Culture Meets Digital Humanities

Sarah Werner

Discussions about early modern books and digital tools have tended to focus on one of two responses. One of the first things that people focus on is the amazing access to early modern works that digital tools have given us. Instead of schlepping from library to library across the globe — a series of journeys that many scholars can not easily afford — we can access nearly all extant early modern printed English books, and many continental ones, from our desktops. Thanks to digital collections like EEBO (Early English Books Online) and ECCO (Eighteenth Century Collections Online) and to catalogs like the USTC (Universal Short Title Catalogue, which links to images from many European collections), digital facsimiles are available for us to consult and download entire works from the early modern printed world.

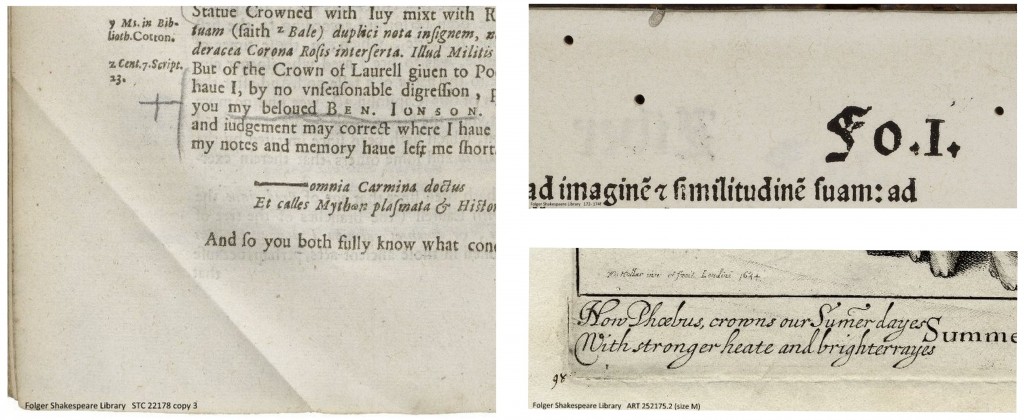

There are limitations, of course. One is the quality of the images. EEBO consists of digital facsimiles not of early books, but of microfilms of early books. As a result, it doesn’t always capture what we might want it to.

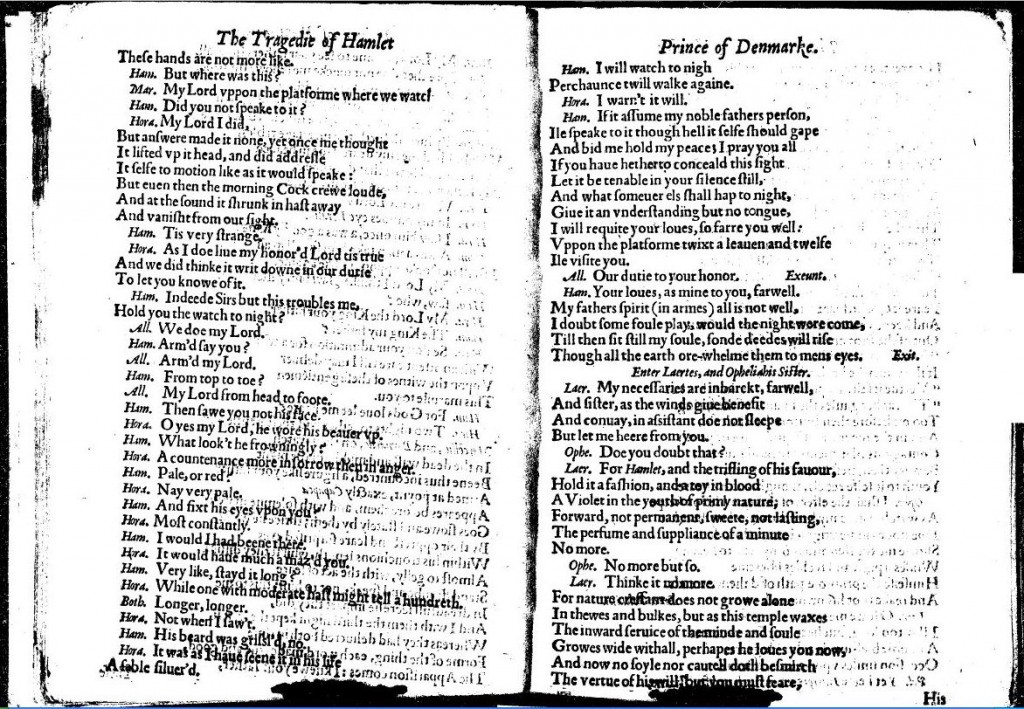

Above is an image from EEBO of the second quarto of Hamlet (STC 22276). You can see one column of text on each page, along with a whole bunch of other junk. Here’s the same page opening from the Folger’s reproduction of that book:

Same Opening, Same Copy, in a High Resolution Image From the Folger

(Click to Open the Full Play)

Image Used by Permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library

There’s still ink bleeding through from the other sides of these leaves, but it’s a bit easier to sort out what’s what.

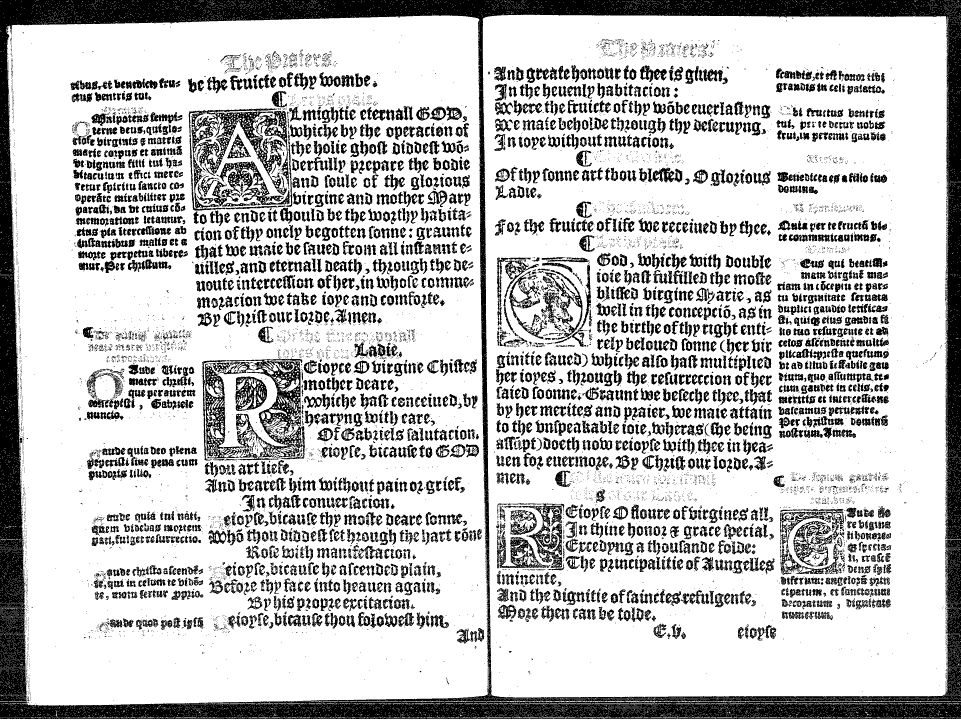

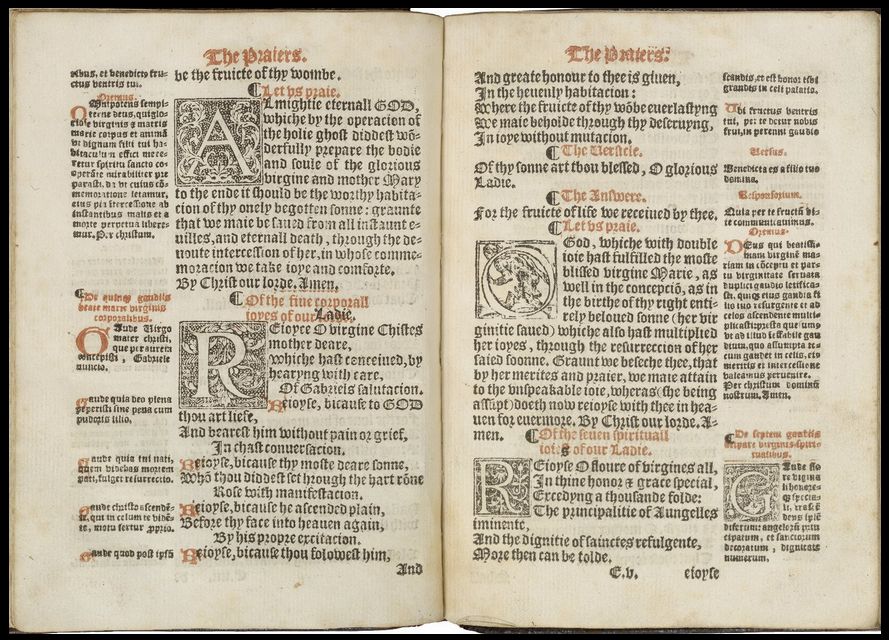

Or compare the reproduction of ink in this pair of images:

Same Opening, in a High-Resolution Image from the Folger

(Click for Zoomable Image)

Image Used by Permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library

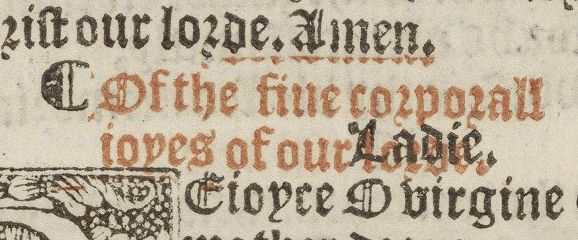

Because the red ink isn’t visible in EEBO, you miss the dynamics between how the different categories of text play out on the page and what they might signal about the book’s use. You also miss what’s really a great mistake, the moment where the phrase “of the five corporall joyes of our Ladie” is really a correction for the mistaken “joyes of our lorde.”

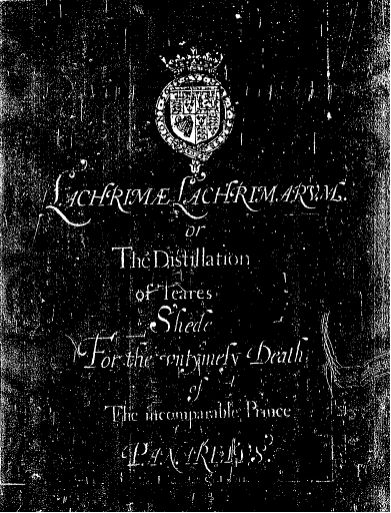

My favorite EEBO moment, however, is this one: the title page of a 1612 elegy mourning the death of Prince Henry. This is how the image appears in EEBO . . .

. . . but this is how the image appears in their reproduction of the second state of this edition:

Lachrimæ Lachrimarum is a mourning book, and it was printed on pages bordered in black and sometimes entirely in black, with a xylographic title page (a title page in which white lettering appears on a black background). But when the microfilm was being processed, someone clearly didn’t believe what they were seeing and they assumed it was a mistake, that it should be black on white.[1] And so they reversed the negative, producing a facsimile of a book that doesn’t exist.

I have been complaining about the quality of reproductions here, and cost is a limitation as well.[2] But digital tools have, without a doubt, increased our access to facsimiles of early modern books. If I can sit in my study outside of Washington, D.C. and study Erasmus’s 1516 translation of the New Testament by looking at a copy currently held in Basel, that’s a win.

If one dominant way of thinking about digital tools and early modern books is in terms of access, another has been in terms of text. Access is about text, of course — what we’re gaining access to is the ability to read texts. But there are also digital tools that don’t simply read texts, they distant read them. EEBO-TCP can make research a bit easier if you’re interested, say, in sassafras and want to find instances of it being discussed. In the right hands, you can do much more interesting types of computational analysis that can reveal things that would be difficult to see otherwise. Recent work by Michael Witmore and Jonathan Hope, for instance, reveals that genre is marked not only in terms of plot, but also linguistically at the sentence level — histories and comedies and tragedies are genres that are grammatically inflected. That is surely a win, too.

The tools that I’ve just described rely on the ways we have always read books, albeit with increases in distance or speed (you can read a book held at the Folger without leaving your study in Gdansk; you can analyze the texts of the entire Shakespeare corpus in a matter of minutes rather than years). But I want to wonder what new possibilities we might imagine. How might we use digital tools to look at texts differently? How might we use digital tools to represent texts differently? Can we move away from reading text to studying the physical characteristics of text, characteristics that can reveal important information about the content of the text and the cultural and historical creation of the artifact?

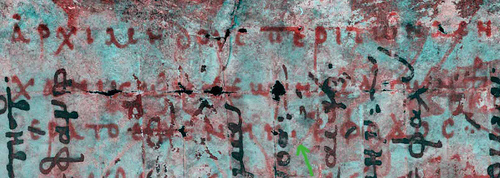

A Digitally Enhanced Image from Archimedes’s Palimpsest

(Copyright: the Owner of the Archimedes Palimpsest. Licensed for use under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Access Rights.)

The multi-spectral imaging done by the Lazarus team of the Archimedes Palimpsest gives a hint of how digital tools might let us see things that would otherwise go unseen. The Archimedes Palimpsest is a 13th-century Byzantine prayerbook written over a 10th-century manuscript containing writings of the Greek mathematician Archimedes, as well as multiple other works from various periods. Using multi-spectral imaging, along with other tools, the team was able to recover visual access to much of the earliest writings in the book. Google took the project’s dataset and made a “Google book” of the earliest state of the codex resulting in a digital reproduction of a book that exists, but is not visible to us just by looking at it.

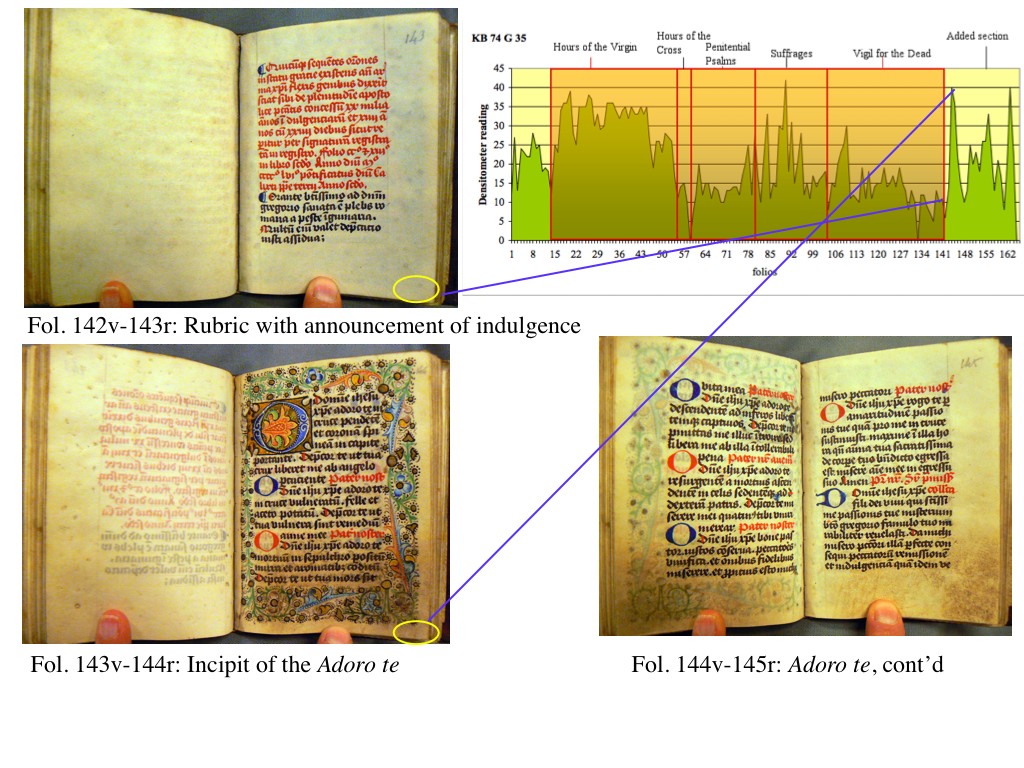

One recent paper about the use of densitometers to study levels of dirt on the pages of medieval manuscripts suggests that we can learn about book usage through analyzing how and where dirt is distributed across a book. It might seem obvious that pages that are used more often will be dirtier, and that is in part what the author found, but the use of the densitometer revealed that it’s more complicated than we can always assess with the naked eye. The paper’s author, Kathryn Rudy, points out, for example, that she had assumed that two different patterns of dirt on an opening came from two different users, but the densitometer’s analysis suggested that the patterns were similar enough that they were likely to have been made by the same person using two fingers to touch some pages rather than one. The analysis also pointed out that even books that retain visible marks might have been cleaned by modern owners to such a degree that the dirt is no longer viable as an analytical tool, something that might help us think about the changes books undergo during modern ownership.[3]

A Comparison of the Levels of Dirt Left on Leaves of a 15th-Century Book of Hours

(Image Courtesy of Kathryn Rudy)

Studying the distribution of dirt is just the beginning of how we might begin to use technology to help us understand books in new ways. A colleague in Antwerp reports that German books held in Belgium smell different than German books held in Germany. The cause lies in how the paper was treated: paper needs to be treated with sizing agents so that it handles ink properly (instead of absorbing ink, ink sits on the surface of the paper and dries there, producing crisp and legible marks). His speculation is that books in Germany were sized in a multi-stage sequence, with the last step taking place after the book had been printed, perhaps as part of the binding process. Books that remained in Germany after they were printed went through this final process; books that were shipped outside of Germany seem to have missed that final stage, resulting in a noticeably different smell because of their different chemical properties. If this is the case, the smell of early German books can help scholars understand not only the physical acts of making paper and books, but can help us trace the circulation of early printed works. Using computers to analyze the smells of books and software to map those smells could help researchers learn how books were made and sold and used.

We could also use new technologies to explore the other senses we use when handling books. The feel of paper (or parchment) is another element of books that has more to offer than nostalgic fetishizing: the thickness, color, and pliability of paper can tell us about the costs of production, in part, but also give insight into the experience of using the book and its intended audience. How might the characteristics of feel be represented in digital media? Could a 3D printer replicate samples of different paper qualities? Could we project back from a paper’s physical characteristics today to how it might have appeared and felt when it was made?

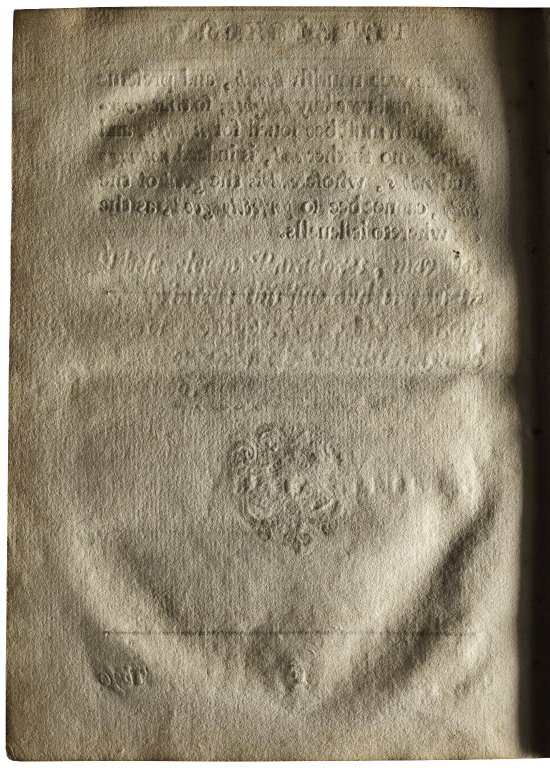

The three-dimensional aspects of paper extend beyond what can be felt by human touch. The process of making books in the letterpress period was a process of putting pressure on the paper, leaving behind an indentation on one side of the leaf and an extrusion on the other side of the leaf. In most cases, the indentations are visible because the instrument causing them (type, woodblock, stylus) left behind ink markings. In other cases, there are indentations without ink, sometimes caused when two sheets of paper are accidentally run through the press, sometimes left behind when the bearing type used to even out the blank spaces in a page leaves behind blind impressions.

There are also the indentations left behind during the papermaking process from the wires and frames used in the forms. Once we start thinking in these terms, we can find more topographical variations on leaves of paper: wormholes, dog-eared corners, holes left from stitches sewing gatherings and the binding together, plate marks from engravings. What might we learn from visualizing books not as texts to be read but as topographical maps?[4] The project to conserve The Great Parchment Book, a 1639 volume of records that was heavily damaged in a 1786 fire, works from the opposite perspective, using digital tools to virtually flatten a badly warped manuscript that cannot otherwise be read.

Folger STC 7043.2, Leaf F1v Under Raking Light

(Click to See a Zoomable Version of this Image Compared to One Under Normal Light)

Image Used by Permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library

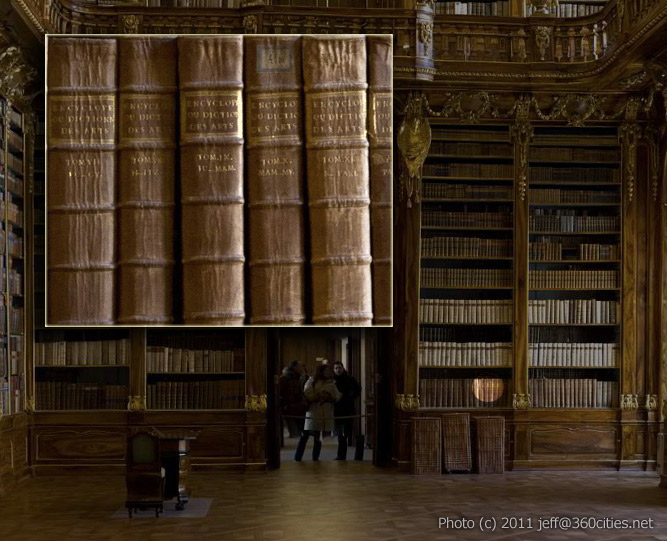

Another option would be to use digital tools to visualize the context of books, to encounter them not in isolated codices, but in libraries. This 360° panoramic view inside the Strahov Monastery’s Library in Prague lets you see not only the entire room, but to zoom in to see the titles of the books on the shelves.

This example is primarily a pretty picture, but imagine if this technology was married to something that let you look at catalog records of the books that you’re seeing, or to switch from catalog records to a view of a book on a shelf. Could we rearrange the books on the shelves, grouping them by accession order, or the chronological order of their bindings, or by their provenance?

If we could use digital tools to estrange ourselves from our books, to defamiliarize what we think we know, we might learn something new about how they were made and how they are used. People keep pointing out to me that we are in the incunabula age of digital texts. We are. And replicating the familiar makes sense in the cradle days of digital texts. But let’s not limit ourselves to reading the digital in the same ways we’ve always been reading.

This paper was given first as a talk at the University of Maryland “Geographies of Desire” Conference on April 28, 2012. It was originally published by Sarah Werner on April 29, 2012 and was revised for the Journal of Digital Humanities in August 2012.

- [1]Ian Gadd first pointed out this example to me.↩

- [2]There are resources that provide higher quality digital facsimiles of early modern books and that, unlike EEBO and ECCO, are free to use. The Folger Shakespeare Library has digitized many works in their entirety, including all copies of the pre-1642 Shakespeare quartos and a couple of first folios. The British Library has digitized some of their collection, cover-to-cover, as have many other libraries, including that of the University of Pennsylvania, Princeton University, University of Oklahoma, and the Bavarian State Library. The English Broadside Ballad Archive now includes some high-resolution color facsimiles, and the Universal Short-Title Catalogue (covering all books printed in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries) includes links to digital copies from many European libraries.↩

- [3]Kathryn M. Rudy, “Dirty Books: Quantifying Patterns of Use in Medieval Manuscripts Using a Densitometer,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 2:1-2 (2010). http://www.jhna.org/index.php/past-issues/volume-2-issue-1-2/129-dirty-books.↩

- [4]Randall McLeod’s work has helped me see the possibilities of thinking about printed books as textured objects. See, in particular, R. MacGeddon, “hammered” in Negotiating the Jacobean Printed Book, ed. Pete Langman (Farnham, Surrey, England; Burlington, VT, USA: Ashgate, 2011), 137-199.↩