An Electric Current of the Imagination: What the Digital Humanities Are and What They Might Become

Andrew Prescott

It is a great honour for me to become head of this academic department devoted to the study of the digital humanities. When I first saw experiments in the digital imaging of books and manuscripts in the British Library twenty years ago, it was impossible to imagine that they would develop into an intellectual activity on a scale warranting an academic department. The fact that King’s College London has led the way in this process is due to the work of many pioneers, and I cannot start this lecture without acknowledging their achievements and saying what a pleasure it is to join them now as a colleague. Above all, it is essential to honour the contribution of Professor Harold Short who is without doubt the father of the Department of Digital Humanities at King’s College London. Harold has been an outstanding international pioneer of the digital humanities, and I feel honoured and humbled to follow in his footsteps.

The work you see displayed here is a digital poem called Birdsong Compliance by the British poet John Sparrow. The words are taken from interviews with the composer John Cage and the critic Joan Retallack. This poem illustrates how some artists have become fascinated by the way digital processes can be used to transform texts into new pieces of art. In Birdsong Compliance, two overlapping texts interact with each other. One text is static while the other moves around this background to create random juxtapositions suggesting new and unexpected meanings.

Another poet very interested in processes by which texts can be transformed or, as he prefers it, deformed in order to discover new meanings is my former colleague at the University of Glasgow, Jeffrey Robinson. Jeffrey is not only an interesting poet but also a distinguished scholar of the Romantic period.

In his recent volume of poems called Untam’d Wing, Jeffrey takes the great monuments of Romantic poetry on which he has worked for many years, and subjects them to processes of poetic transformation. He reduces Wordsworth’s sonnet Composed upon Westminster Bridge to five key words conveying the ecstasy of a scene witnessed by early morning light. Jeffrey splices lines and phrases from the poetry of Keats, Wordsworth and Coleridge with lines from Ezra Pound, Robert Lowell and Gertrude Stein. Jeffrey finds new poems in marginal notes by Keats. He takes lines from famous sonnets of the Romantic period and mixes them up to create new sonnets which reveal surprising interrelationships between the words, rhythm and imagery of the originals. Jeffrey riffs on phrases and words in individual poems, setting out like a jazz musician to renew a body of standard work (in the way that, say, Miles Davies might revisit George Gershwin).

The effect of Jeffrey’s deformations and transformations of romantic poetry is at first disconcerting, then magical. Jeffrey’s reworkings compel us to look afresh at individual words and lines. Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem The Eolian Harp, originally published in 1795, has often been taken as the beginning of the Romantic movement in poetry. I have given the text of the first section of The Eolian Harp on your handout. Over the page, you can read one of Jeffrey’s deformations of The Eolian Harp, which picks out words from Coleridge’s poem. I have known The Eolian Harp since I was a teenager, but it wasn’t until I read Jeffrey’s version of it that I really noticed Coleridge’s use in this poem of the startling word ‘sequacious’. This word, rarely used in English poetry, meant in the seventeenth century ‘following a leader slavishly’. By the eighteenth century, ‘sequacious’ came to be used with reference to objects, and mean pliability or flexibility. Applying the word to the ethereal sound of the Aeolian harp, Coleridge here gives ‘sequacious’ a further musical inflection.

Jeffrey Robinson’s poems encourage us to focus on the evanescence of individual words like ‘sequacious’, which we might otherwise skip over. Jeffrey reminds us that new insights can be found in single words just as much as in huge quantities of data. Robinson’s juxtapositions of the old and the new seek, in his words, to generate ‘an electric current of the imagination (as the Romantics might put it) [which] causes transformations that constitute a real thing in the world’.

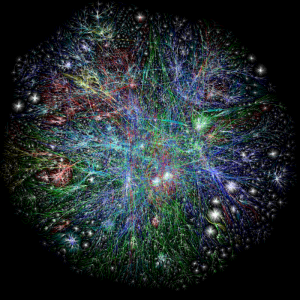

This is an image from the OPTE project which was started by Barrett Lyon in 2003 and seeks to create a visual representation of the internet. This image represents the internet connections of a single computer in November 2003. The purpose of the OPTE project is to map the growth of the internet, to identify gaps in the internet’s structure, and to analyse the effect on the internet of major events such as wars and natural disasters. But the images are also aesthetically pleasing, and they have been displayed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This image conveys something of the scale of the internet, but gives little sense of its growth over the past fifteen years. In 2000, there were about 361 million internet users. Since then, the number of users has grown four fold, so that there are currently just over two billion internet users, about one third of the world’s population. There are currently estimated to be about 12 billion indexed pages on the indexed World Wide Web (and how odd that our unit of measurement for the web continues to be the page).

In 1997, Michael Lesk calculated that the entire holdings of the Library of Congress amounted to about 20 petabytes of data, and guessed that the total information in the world amounted to a few thousand petabytes. By 2003, Lesk reported that the total of new information created every year amounted to 1.5 exabytes, which is over 1500 petabytes or 1.5 billion gigabytes. As of May 2009, the size of the world’s total digital content was estimated at 500 exabytes or over a trillion gigabytes – about 160 gigabytes for every man, woman or child on earth, or about 480 gigabytes for each internet user. Most of this information has been created since 1997. It is also estimated that during the single year 2013 internet traffic will be equivalent to all the information currently in existence.

These figures are dizzying and perhaps rather terrifying. Michael Lesk also calculates that the works of a single author such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge or Wordsworth occupy about one hundred megabytes of data, not so much a drop in the ocean of information, as an atom in a universe of data. How in this context are we to hang on to the resonances and evanescence of a single word in a single poem like ‘sequacious’? In this huge and inhuman world of information, poems start to look as fragile as butterfly wings.

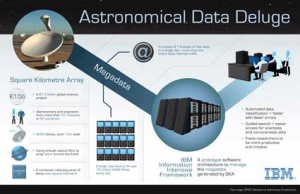

Scientists frequently deal with vast and intimidating problems of information. When the Square Kilometre Array, a sophisticated radio telescope, is built, it will produce four petabytes of data an hour. Each day, the Square Kilometre Array will process more information than is found in all the printed books in the world’s national libraries. Although film and video can for example generate large quantities of data, humanities scholars in general do not at present confront the same problems of scale of information that astronomers have to deal with. Humanities scholars are often much more preoccupied with the complexities of the smaller scale – with the problem of a word like ‘sequacious’. Nevertheless, in their approach to information, humanities scholars have tended to use approaches more appropriate to the large quantities of data dealt with by scientists. The main concerns of humanities computing have been with such issues as the modelling of data, its interoperability and sustainability, and the control and management of its growth. Yet many of the books, manuscripts, pictures, films sound recordings and artefacts with which humanities scholars are concerned resist such managerial approaches – they are messy, damaged, ambiguous in their meaning and complex in their structure. They refuse to be sequacious.

Among the many commercial online packages on which humanities scholars and students have become increasingly reliant is Literature Online, which is produced by Proquest and contains a fully searchable library of more than 350,000 works of English and American poetry, drama and prose. Here is how The Eolian Harp appears in Literature Online, and this is nowadays likely to be the way in which many students first encounter the poem. We are presented with the text from the 1912 edition of Coleridge’s Poems, and everything looks reassuringly simple and straightforward. Admittedly this isn’t the most recent and authoritative edition of the poem, which was published by J. C . C. Mays in 2001, but there are problems running deeper than this. A study by Jack Stillinger has emphasized how Coleridge constantly revised and altered his poems, so that there are something like sixteen different versions of The Eolian Harp in manuscript and printed form, all dating from Coleridge’s lifetime. These range from 51 to 64 lines in length. Sometimes Coleridge presented the poem as a single section, and at other times he divided it into three, four or five paragraphs, so that the poem’s development could be more clearly followed. The various versions of the poem have different titles, reflecting Coleridge’s uncertainty as to the best way to convey the poem’s abstract and reflective character. Among the titles with which Coleridge experimented were ‘Effusion XXXV’ and ‘Composed at Clevedon, Somersetshire’, and he only settled on the title ‘Eolian Harp’ in 1817. Stillinger comments: ‘There are too many differences [between these versions] to enumerate… they change the tone, the philosophical and religious ideas, and the basic structure rather drastically. The first recoverable version, ‘Effusion XXXV’, recounts an amusing incident of early married life, while the latest version is a much more serious affair’. Many of Coleridge’s poems are characterized by this textual instability – Stillinger calculates that there were at least eighteen different versions of The Ancient Mariner. In this context, we might wonder how far there was ever a single settled version of a poem like The Eolian Harp or The Ancient Mariner. Jeffrey Robinson’s process of ‘deforming’The Eolian Harp can be seen as the continuation of a process in which Coleridge himself engaged for more than twenty years.

Users of Mays’s monumental edition of Coleridge’s poetry immediately realize how important this textual instability is in understanding both Coleridge and his poetry. The wealth of evidence for the changes in particular texts led Mays to divide his edition between, on the one hand, reading texts and, on the other, a bewildering variorum edition. In the case of The Eolian Harp it was even necessary for Mays to include in the Variorum edition photographs of annotated copies of Coleridge’s 1817 collection, Sibylline Leaves, illustrating Coleridge’s continued reshaping and development of his poem, and I have included one of these in your handout. None of this is even hinted at in Literature Online or other online presentations of the poem. Literature Online irons out the complexities and uncertainties of The Eolian Harp and reduces it to a piece of information which could be transmitted by telegraph. There is an irony here in that cultural commentators frequently emphasise the (often false) perception of online information as inherently ephemeral, volatile and unstable. Yet here the online version presents a very fixed image of a text that is, in its manuscript and printed version, very volatile and unstable. This instability reflects Coleridge’s attempts to replicate the fluidity and interconnectedness of conversation, and so is important in understanding the poem. These are precisely the issues we need to confront in considering the humanities in an information world: how to represent flux and fluidity, how to explore instability and uncertainty, how to represent the complexity of the minute. Scientists want to map the universe; humanities scholars want to investigate the universe contained in a single poem. And, as Coleridge’s work demonstrates, that poem may turn out to be more complex in its structure and interconnections than an entire galaxy.

We have been here before. This is a celebrated scene of the early industrial revolution at Coalbrookdale in Shropshire. A sense of being overwhelmed by technology, of anxiety about the way in which new technologies are transforming society, while at the same time feeling excited at the material improvements which these changes might bring is a familiar – perhaps even a necessary – condition of modernity. A standard point of historical reference in thinking about the modern information revolution is the arrival of print in the fifteenth century, but perhaps a closer parallel is the way in which the growth of empire and the resulting changes in industry and agriculture transformed Britain in the late eighteenth and nineteenth century. David Simpson has pointed out how Wordsworth’s reference to ‘bright volumes of vapour’ in his poem ‘Poor Susan’ in the Lyrical Ballads may refer to the over-production of cheap and worthless literature – a data deluge whose effects preoccupied Wordsworth. The prostitute Susan in Simpson’s interpretation is one of an army of alienated and rootless people who pervade Wordsworth’s verse: beggars whose anxious movements reflect the pointless and repetitive movements associated with the introduction of machines; vagrant farmworkers who have been disconnected from the land by enclosure; discharged soldiers who move through the landscape like ghosts. Concerns about the nature of the society emerging at that time united such disparate figures as Burke and Cobbett. Burke fretted that the state was becoming ‘nothing better than a partnership agreement in trade of pepper or coffee, calico or tobacco, or some other such low concern, to be taken up for a little temporary interest, and to be dissolved at the fancy of the parties’. From a completely different stance, Cobbett expressed his horror at the way in which the cash nexus was becoming all pervasive: ‘We are daily advancing to the state in which there are but two classes of men, masters and abject dependents’.

Part of our role as scholars of the digital humanities should undoubtedly be to challenge those glib historical claims frequently made about modern developments in information technology. A longer historical perspective suggests that today’s developments are but another step in a long revolution in in the structuring of knowledge and its representation. The invention of the codex at the beginning of the Christian era was just as remarkable as the appearance of the iPad. The creation of the biblical concordance in the twelfth century was equally revolutionary – the idea that sacred text could be broken up according to an external and abstract pattern of alphabetization verged on the sacrilegious. Without the Western adoption of Arabic conceptions of zero at about the same time, digitization would have been still born. And of all the mechanical inventions which transformed human life, few have had greater impact than the appearance of the mechanical clock in the thirteenth century. In the nineteenth century, factories and railways transformed the very structure of time. Each age has had its information revolution, but nevertheless it seems that what happened at the end of the eighteenth century dwarfed them all. We can see this by the way in which reactions to those changes which so alarmed Wordsworth, Coleridge, Burke and Cobbett are still evident in our everyday language.

In his seminal work Culture and Society, Raymond Williams described how the great social and economic changes in Britain between 1760 and 1830 resulted in the development of new meanings for such key words as class, industry and artist. For example, the idea that the terms art and artist refer to the imaginative or creative arts first appears in this period, and was an attempt to affirm essential spiritual values in the face of the dehumanizing effects of the industrial and agricultural revolutions. Of these major ideological and conceptual shifts at the time of the Industrial Revolution, Williams singled out as particularly significant that term which has become a modern intellectual catch-all: culture. The modern concept of culture as meaning a general body of artistic achievement and activity and, eventually, a whole way of life was, again, a reaction to the appearance of modernity. Williams traces a tradition running from Burke and Cobbett through Romantic artists such as Coleridge and Wordsworth through to John Stuart Mill and Matthew Arnold, and still evident in twentieth century commentators such as Eliot and Leavis, which articulates the idea of culture as a mechanism for preserving essential human values in the face of a society increasingly dominated by trade, manufacture and the earning of a living. Coleridge is a pivotal figure in this development, declaring to Wordsworth that there was a need for ‘a general revolution in the modes of developing and disciplining the human mind by the substitution of life and intelligence for the philosophy of mechanism which, in everything that is most worthy of the human intellect, strikes Death’. In his Essay on the Constitution of the Church and State Coleridge called for the creation of an endowed class known as the Clerisy or National Church whose business would be ‘general cultivation’. The Clerisy would consist of ‘the learned of all denominations: the sages and professors of all the so-called liberal arts and sciences’. Coleridge had a profound influence on the early development of King’s College London and may in many ways be seen as its presiding genius.

The idea of the humanities was at the heart of this early nineteenth century debate about resisting that mechanistic Utilitarian society which so entranced figures like Jeremy Bentham. Coleridge declared that his Clerisy would counter this mechanistic death of the spirit. The Clerisy would ‘remain at the fountainhead of the humanities, in cultivating the knowledge already possessed, and in watching over the interests of physical and moral science’. The humanities are thus another of those keywords which reflect the ideological shifts associated with the rise of modern society. Just as the definition of art shifted, so the older form of the word humanities, associated with the study of the litterae humaniores was discarded and replaced by a focus on that knowledge which would encourage, in Coleridge’s words, ‘ the harmonious development of those qualities and faculties that characterize our humanity’. Coleridge declared that his intention was to undo the entire philosophical and scientific superstructure associated with the measurement and geometry of the Newtonian world. In his view, this mechanistic concern with numbers and measurement threatened to destroy the life of the mind and crush the human spirit. The humanities were a reaction against modernity, and an affirmation of the human spirit against the cash nexus.

In this context, the idea of the digital humanities is problematic. At one level, the computer is simply a sophisticated spinning jenny. Indeed, the great-grandfather of the computer, Babbage’s difference engine, with its programmes developed by Ada Lovelace from the mechanisms used to control looms, was the most sophisticated and forward-looking product of the first phase of the Industrial Revolution. The present information revolution could be seen as an attack by the heirs of Babbage on the very cultural arena established as a refuge against the mechanistic impulse. If we see the digital humanities as merely extending mechanistic arithmetical procedures into the realm of cultural endeavour then they indeed mark that death of the spirit which Coleridge so much feared. Alan Liu has brilliantly described in his Laws of Cool how modern computing is an instrument of that managerial impulse which seeks to make knowledge work as mechanical and controlled as work on a production line. Liu reminds us how the aesthetics and language of computing, with its excitement about the latest ‘cool’ medium, are a refuge from the grim reality of a cubicle in an open plan office on an industrial estate. In the end, Liu sees the digital humanities as an escape from the tyranny of the cool, but there is a sense of despair in his conclusion that the only reaction to art in such a situation is to deform and deface it, in a way which anticipates some of Jeffrey Robinson’s procedures in Untam’d Wing. The work of Liu and other commentators reminds us that the modern information revolution is not simply about machines and the capabilities of new technology. It is about how knowledge is being turned into a commodity, a data steam disconnected from those who produce it and turned to commercial advantage by monopolistic corporations. This is surely something which must be resisted, but it will not be achieved by using open source software or even by engaging in a strategy of resistance. We need precisely what Coleridge called for in his letter to Wordsworth: ‘a general revolution in the modes of developing and disciplining the human mind by the substitution of life and intelligence for the philosophy of mechanism which, in everything that is most worthy of the human intellect, strikes Death’. This cannot be achieved by escaping the digital; there is no escape from the digital, any more than there was from the industrial revolution. What is necessary is to reshape the digital world in Coleridge’s model. The creation of such a world is the mission of the digital humanities.

It would be easy to see Samuel Taylor Coleridge as opposed to science. However, as Nicholas Roe and others have recently emphasized, Coleridge was deeply preoccupied with science. He sought to ‘warm his mind with universal science’ and declared ‘I would be a tolerable Mathematician, I would thoroughly know Mechanics, Hydrostatics, Optics and Astronomy, Botany, Metallurgy, Fossilism, Chemistry, Geology, Anatomy, Medicine’. The Eolian Harp was partly prompted by Coleridge’s reading of materialist scientists such as Thomas Beddoes and Erasmus Darwin, and for Nicholas Roe the poem demonstrates that ‘for Coleridge at this moment there was no separation between imaginative writing and advanced science or ‘natural philosophy’. Coleridge’s preoccupation with science reflected his concern that physicians such as John Hunter only offered ‘mechanical solutions’ to the understanding of life. In 1824, Coleridge supplied notes on the ‘Idea of LIFE’ for Joseph Henry Green, who afterwards became the first Professor of Surgery here in King’s College London. For Coleridge, then, the first step in resisting the mechanistic spirit of the industrial revolution was a profound engagement with science. Likewise, if humanities scholars wish to ensure that their understanding and engagement with human knowledge does not become another Californian commodity, it is essential to engage with the digital world, and not as consumers but as creators.

This then is the challenge for the digital humanities: to create a new type of humanities which will transform science and technology and achieve a revolution comparable to that revolution of understanding sought by Coleridge. How have the digital humanities risen to this challenge? There can be no doubt that the practice of humanities scholarship has been transformed by the increasing availability of digital tools and resources over the past ten to fifteen years. A recent study by Mark Greengrass and Stephen Brown found that 89% of a sample of 149 humanities researchers used the Web on a daily basis and 77% had been using the Web for five years or more. Likewise, in the LAIRAH study, 81% of a sample of humanities researchers identified themselves as extensive users of digital resources, and 83% agreed that digital resources had changed the way in which they did their research. However, these studies also indicate a problem for the digital humanities. Overwhelmingly, the digital resources used by humanities scholars are commercial packages produced by libraries and digital publishers such as Eighteenth Century Collections Online, Early English Books Online, Literature Online, or JSTOR. Usage of the specialist packages produced by digital humanities centres based in universities is, by contrast, very low. For many humanities scholars, the most pressing need in developing digital infrastructures is not to increase engagement with the digital humanities but rather to secure access to commercial packages which their institutions cannot afford, such as the monstrously expensive Parker Library on the Web.

The digital revolution has occurred, but its course was dictated by libraries and commercial publishers, and the digital humanities as formally constituted has largely stood on the sidelines. The well-known digital humanities centres in British universities such as King’s, Glasgow, Sheffield and Belfast have of course produced dozens of digital projects over the years, but the impact of these has generally been very limited compared with the major commercial packages. A great deal of effort has gone into developing subject associations for the digital humanities such as the Association of Literary and Linguistic Computing and the Alliance of Digital Humanities Organisations, but these look increasingly irrelevant and marginal to wider digital scholarship. The international Digital Humanities conferences are, as Jerome McGann has recently emphasized, preoccupied with inward-looking discussion on metadata and standards, and seek to establish what McGann calls ‘tight little disciplinary islands; tight little techie islands’. Patrick Joula has recently produced a devastating analysis of academic journals for the digital humanities, showing that they are rarely cited by other scholars and fail to attract contributions from scholars in leading universities. The digital humanities consistently punch beneath their weight.

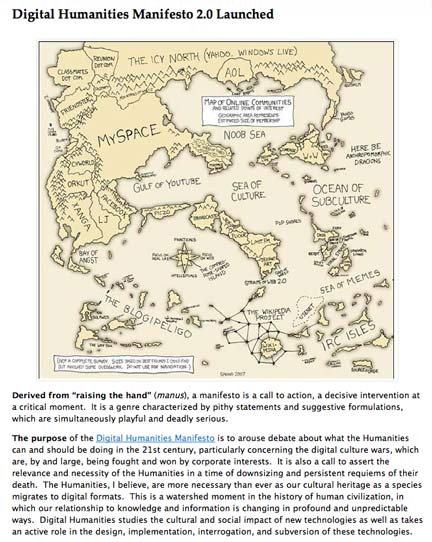

There are signs of change on the horizon. The enthusiasm for the digital recently evident at major subject conferences such as MLA and the American Historical Association has received a great deal of publicity, but perhaps this is just another example of the digital humanities being proclaimed yet again as the next big thing, as has happened many times in the past. More exciting is the work of new groups such as HASTAC, which has been very successful in attracting to the digital humanities large new communities of young scholars who are not only culturally and critically engaged but also emphatically wired. It is striking how many of these younger scholars reject the older institutional structures of the digital humanities and seek, as a recent twitter and blog discussion urges, to transform DH. The case for a new digital humanities is also proclaimed in the “Digital Humanities Manifesto 2.0” drafted by Todd Presner, Jeff Schnapp and others, which declares that ‘The first wave of digital humanities work was quantitative … the second wave is qualitative, interpretive, experiential, emotive, generative in character’.

Despite these recent bursts of optimism, however, the record of the digital humanities remains unimpressive compared to the great success of media and culture studies. Part of the reason for this failure of the digital humanities is structural. The digital humanities has struggled to escape from what McGann describes as ‘a haphazard, inefficient, and often jerry-built arrangement of intramural instruments, free-standing centers, labs, enterprises, and institutes, or special digital groups set up outside the traditional departmental structure of the university’. Such structures, McGann observes, ‘are expensive to run and the vast majority of the faculty have no use for them’. The only answer is to move these various labs and centres into the main academic structure, and this is why the decision by King’s to establish its long-standing Centre for Computing in the Humanities as an academic department and to merge its Centre for e-Research into the Department is very important. A second problem is that the digital humanities has not generated an intellectual programme and, more particularly, a teaching agenda comparable to the work of (say) Thomas Tout in pioneering history programmes at the University of Manchester at the beginning of the twentieth century or Leavis and Richards in creating the study of English literature in Cambridge in the 1930s or more recently Richard Hoggart at Birmingham in developing cultural studies. Pioneers like Leavis or Hoggart did not lack ambition for their new subjects. Both Leavis and Hoggart felt that their new academic disciplines would generate major social and cultural reforms. In the digital humanities, we need to emulate the ambition of a Leavis or a Hoggart and create new teaching programmes articulating new intellectual and social aspirations. I hope that a priority for King’s over the next few years will be to develop a single honours undergraduate programme in the digital humanities which will enable us clearly to set out our overall intellectual agenda.

In America, the growth of digital humanities has often been linked to English Departments, and Matthew Kirschenbaum has given a fascinating account of ‘What Is Digital humanities and What’s It Doing in English Departments?’ In Britain, digital humanities has struggled to find a similar relationship with an academic discipline. It has often developed from libraries and information services and it is frequently seen as a support service. One of the things that I am proudest of in my career is the way in which I have moved between being a curator, an academic, and a librarian. Museums, galleries, libraries, and archives are just as important to cultural health as universities. Indeed, I have found my time as a curator and librarian consistently far more intellectually exciting and challenging than being an academic. Institutions such as the British Library, the British Museum, the National Archives, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the House of Lords Library contain communities of scholars who possess the skills and understanding that will be essential to our society in negotiating a new digital order. I am particularly delighted tonight that my audience includes scholars from all these institutions. Digital innovation is more likely to come from libraries and information services than university departments. One of the great tragedies of university life in recent years has been the way that a distinction has grown up between ‘academic’ and ‘non-academic’ staff, so that for example research active staff in university libraries are no longer eligible for return to the REF, effectively excluding from the academy precisely those people who are most needed by it at the moment. With the collapse of American academic job structures in recent years, there has been a great deal of talk about ‘alternate academic careers for scholars’ or alt-ac as the twitter tag puts it. But I worry that this suggests that libraries or museums are a kind of second best to universities. Far from it – libraries, museums, galleries should be at the heart of the academy. An important current experiment in this area is at the National Library of Wales, where the Chair of Digital Collections of the University of Wales is based within the Library. I am delighted that the holder of this first digital humanities chair based in a cultural institution is Lorna Hughes, previously from King’s, and we look forward to working closely with Lorna.

The ‘Digital Humanities Manifesto’ declares that ‘Whereas the modern university segregated scholarship from curation, demoting the latter to a secondary, supportive role, and sending curators into exile within museums, archives, and libraries, the Digital Humanities revolution promotes a fundamental reshaping of the research and teaching landscape. It recasts the scholar as curator and the curator as scholar’. I think that hits the nail on the head as to what the digital humanities could become. The process whereby the curator became disconnected from the academy is a mysterious one, and deserves more study. When Frederic Madden, the great Victorian manuscript scholar, was prevented by family circumstances from pursuing his academic studies at Oxford, an appointment as an Assistant Librarian at the British Museum placed him at the heart of Victorian literary and historical scholarship. Likewise, Antonio Panizzi’s appointment to the British Museum in 1831 was a definite step up from his uncertain position as a Professor of Italian at University College London. It is a paradox that, in the late nineteenth century when modern scholarship was stressing the importance of rigorous documentary and textual analysis, the relationship between academic scholars and curators became fatally weakened. By the 1920s Sir Walter Greg and others were lamenting the failure of universities to undertake systematic work in descriptive bibliography. A similar story can be told of palaeography. Although Maitland declared at the beginning of the twentieth century how all history has been rewritten because of the study of manuscripts in libraries, and notwithstanding the initiative of King’s College in appointing Hubert Hall of the Public Record Office to a Chair of Palaeography in 1919, provision for teaching in palaeography has always been patchy. Palaeography has found it difficult to escape the stigma of being an ancillary discipline – something to be got out of the way before one got on with the real research. I look forward to working with our newly appointed Professor of Palaeography and Manuscript Studies, Professor Julia Crick, in trying to address these issues.

Yet, despite the semi-detached relationship of disciplines like bibliography and palaeography with the academy, they should be recognized, as Matthew Kirschenbaum has reminded us, ‘as among the most sophisticated branches of media studies we have evolved’. Digital humanities offers a means by which disciplines such as bibliography, palaeography, diplomatic and museum studies can be brought back to the heart of the academy. Moreover, at the heart of these disciplines is the perception that our understanding of knowledge is inextricably bound up with the nature of the medium by which it is transmitted to us. The cultural threat of the digital lies in its commodification of knowledge – the way in which (as Robert Darnton has eloquently described in the case of the Google Book Settlement) knowledge is being turned into a monopoly generated and owned by private corporations. Yet this is only a risk if we see knowledge as data and forget its complex material base. The digital humanities should constantly engage with the materiality of knowledge. Kirschenbaum has forcefully reminded us how data is material, and in his grammatology of the hard drive reminds us how data is recorded on a funny whirring object which functions in a way very similar to a gramophone record. The study of such materialities of knowledge requires a much larger and more expansive engagement with science than if we simply see science as data crunching. By forming closer links with such curatorial disciplines as bibliography and palaeography, and connecting these with the theoretical insights of media and cultural studies, the digital humanities can reshape the academy and address those cultural imperatives which confront it.

This digital image is now more than twenty years old, but for me it is an emblem of what the digital humanities can be. In 1731, the great manuscript library of Sir Robert Cotton was severely damaged in a fire. The library was afterwards one of the foundation collections of the British Museum and the unconserved fragments rescued from the fire were preserved in an attic room in the Museum. Sir Humphrey Davy was consulted as to means by which the fragments could be opened up for public use, and a large number of manuscripts were restored, but Frederic Madden was nevertheless horrified to discover in 1837 that thousands of burnt fragments like this one were still preserved in the attic. Madden began a conservation programme for this material which took over twenty years. Yet badly burnt fragments like this one, from an eleventh-century collection of Old English saints’ lives, remained illegible. By 1913, the American forensic scientist Elbridge Stein had demonstrated that ultra-violet light could be used to read damaged writing. In 1934, an ultra-violet cabinet, manufactured by a firm in which the Glasgow scientist Lord Kelvin was a partner, was installed in the British Museum and allowed documents such as this to be read. It was difficult however to get a stable image of the ultra-violet readings.

In the 1980s, my friend Professor Kevin Kiernan was working on these damaged Cotton manuscripts and wondered if there were other scientific methods available which could assist in this study. He was given advice on specialist imaging technologies by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and found the medical imaging equipment could be used to create digital images. He longed to try this new equipment on the burnt Cotton manuscripts. Finally, in 1993, I was able to assist him in getting the necessary access and the medical imaging firm Roche Kontron provided a camera and operator. The result was this image of a phrase in the burnt fragment. Nervous about transporting this image back to the United States only on a hard disc, a second copy was sent by phone modem and as far as I am aware this was the first digital image of a medieval manuscript transmitted across the Atlantic. The initial image was flooded with the blue of the ultra-violet light and required extensive image processing by Kevin to reveal the remnants of Old English script.

This was an experiment which was dependent on collaboration between the scholar, curator, conservator, scientist and imaging technician. We didn’t know whether the imaging equipment would work. The methods we adopted were dependent on scientific advice and guidance. We didn’t know whether the resulting image would ever reach the United States. But we definitely produced important research results.

The history of the Cotton collection has been one of engagement with cutting edge science, ever since Humphrey Davy was consulted about the conservation of the fragments. Since our 1993 experiment, digital imaging of manuscripts has become routine and images under special lighting conditions have been produced of manuscripts ranging from early papyri to the early biblical manuscript, the Codex Sinaiticus, and the eighth-century Chad Gospels. It might be objected that such very specialist imaging techniques are only relevant to very early materials. This slide, however, shows hyperspectral imaging of a detail in one of the most celebrated modern documents, Thomas Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence. This imaging under a variety of light wavelengths by the Library of Congress has recently revealed how, in drafting the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson first used the words ‘fellow subjects’ and gradually altered them to ‘fellow citizens’. A similar project at the National Library of Scotland has recovered the illegible text of David Livingstone’s diaries. There are countless further research projects in this field which require close collaboration between scientist, humanities scholar, curator, and conservator. Thousands of manuscripts were damaged in the nineteenth century by the application of chemical solutions in an attempt to read faint text. The residue of these solutions means that we cannot use the fluorescent effects of ink at different light wavelengths to recover the text. To address this problem requires further research into the chemistry of the ink and manuscripts, which in turn requires closer collaboration with scientists. This is the kind of project which should be at the heart of the digital humanities. The Diamond Light Source, Britain’s national synchrotron science facility, has recently been used successfully to investigate objects ranging from 18th century Spanish manuscripts to Catalan altarpieces. This engagement with ‘big science’ will eventually give birth to a ‘big humanities’ but in order to achieve this we need new forms of dialogue with our scientific colleagues. Such methods are of course familiar in archaeology and art history. The digital humanities must strive to make this creative engagement with cutting-edge science more widespread.

Again, it might be felt that this stress on the materiality of our cultural heritage ignores sound or vision, both of which have become much more readily accessible as a result of digital resources. However, a digital version of the music on a cylinder or record only tells part of the story. We cannot understand the cultural significance of an album like Sergeant Pepper by accessing it on iTunes. The cover of Sergeant Pepper was a celebrated artwork in its own right and even the inner sleeve containing the record added to the overall impact of the album. It is impossible to understand the order and structuring of the music of an album like Sergeant Pepper without knowing that an LP record had two sides, or that there was a lock groove at the end of each side.

Likewise, our understanding of film is inextricably bound up with its material basis. I was very lucky while I was at the University of Sheffield to be a member of a group of scholars who worked on the Mitchell and Kenyon collection, a remarkable archive of films of Edwardian life found in the basement of a shop in Blackburn. The restoration of these fragile nitrate films by the British Film Institute was itself a remarkable feat of scientific conservation. The sense we gain from the Mitchell and Kenyon films of proximity to everyday life was in part due to the fact that only the master negatives of the films survived. Most Edwardian films usually survive only in scratched and damaged copies which increase our sense of distance from the scenes depicted. The clarity of the Mitchell and Kenyon films change our relationship as viewers to these depictions of the past, in a fashion that raises questions about the relationship between viewer, cameraman, participant, and medium.

Coleridge’s The Eolian Harp demonstrates how an engagement with the latest scientist discussion can directly contribute to great art. Jeffrey Robinson has also shown us how scholarship can inspire poetry. Both Coleridge and Robinson remind us that, in this dialogue between humanities scholar, scientist, and curator, the creative artist also has a vital role. Digital art is increasingly breaking down many familiar disciplinary barriers and it has a key role to play in developing the next wave of the digital humanities. I was fascinated on my arrival at King’s to learn about the collaborations between the artist Michael Takeo Magruder and members of the Department of Digital Humanities. Michael’s artwork, Data Sea, created by him for the International Year of Astronomy in 2009 and installed in Thinktank at the Birmingham Science Museum, uses astronomical databases to create a three-dimensional artwork. Michael’s associates in creating this artwork were Drew Baker, for the 3D visualisations, and an astrophysicist, Johanna Jarvis. This is the kind of collaboration which would have delighted Coleridge, and it makes one think of how those vast data flows produced by the Square Kilometre Array may also provide material for artists.

Visualisation techniques may seem like an escape from the material, but they are a powerful way of reengaging with a lost materiality. The Abbey Theatre in Dublin was destroyed by fire in 1951, but a virtual reconstruction by DDH’s Hugh Denard with colleagues from Trinity College Dublin enable the nature of the Abbey as a performance space to be explored and events such as the riot at the first performance of Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World to be investigated in their material context.

Visualisation is thus intimately bound up with the exploration of lost materialities and the recreation of old cultural spaces. An engagement between the virtual and the material is at the heart of this reconstruction by DDH’s Martin Blazeby. It shows a fresco from a Roman villa at Oplontis near Pompeii, and is one of a hundred rooms reconstructed in this way. On the left, you can see the surviving fragments of the fresco, and on the right its reconstruction by Martin.

The work in reconstructing the lost villa at Oplontis has itself become the basis for an artwork by Michael Magruder and Hugh Denard called Vanishing Point(s) which was commissioned for the 2010 Digital Humanities conference and was displayed in the Great Hall here in King’s.

In this and other examples I have shown you, science is used to explore the materiality of our engagement with the past and the nature of our achievements as human beings, thereby producing new art. This is surely the stuff of the ‘universal science’ which Coleridge sought to recreate. Such a new conjunction of scientist, curator, humanist, and artist is what the digital humanities must strive to achieve. It is the only way of ensuring that we do not lose our souls in a world of data.

Originally posted by Andrew Prescott on January 26, 2012.