The Emergence of Literary Diction

Ted Underwood and Jordan Sellers

Literary criticism used to be, in great part, an attempt to define the distinctive character of “literary language.” The project preoccupied Russian Formalists and American New Critics, and dates back to the nineteenth century. In recent years, critics have largely abandoned the attempt to define literary language, since it is now clear that the category of literature itself is historically unstable. But if we could trace the transformation of literary language in a detailed way, this instability might become interesting: we could use the changing characteristics that have marked language as literary to illuminate the transformation of literature as a social category.

What does it mean to say that literature is not a stable category? Up to the middle of the eighteenth century, the word referred generally to writing or learning. The modern definition, restricted to imaginative writing or belles lettres, emerged only gradually between 1750 and 1850. This shift was not merely semantic: it tracked the emergence of new social distinctions between different kinds of status associated with literacy. The new, specifically aesthetic concept of literature supported a newly autonomous model of cultural distinction.[1] Literary cultivation was not to be confused, on the one hand, with ordinary literacy (correct spelling, refined diction) or, on the other hand, with specialized learning. Literature was a special kind of writing founded on elementary human feelings, or on perception itself. Literary cultivation was therefore independent from other forms of refinement — so independent that it could find distinction even in the plain language of “low and rustic life.”[2]

William Wordsworth filed this concept under the name “poetry.” But the new model of literary cultivation he helped define was not restricted to poetry, or to the Romantic era. Novelists similarly idealized fiction by claiming that it captured human experience at its most elemental; the novel was more universal than other forms of writing, according to D. H. Lawrence, because it alone grasped the immediacy of “man alive.”[3]

As a history of critical concepts, this is a familiar story. But critics haven’t yet realized how concretely these new definitions of literature shaped writerly practice. From the middle of the eighteenth century through the end of the nineteenth, poetry, fiction, and drama acquired a new diction that dramatized the difference between literary cultivation and mere specialized learning. This claim is too broad to rest on any single piece of evidence. But we can start by sketching a big picture.

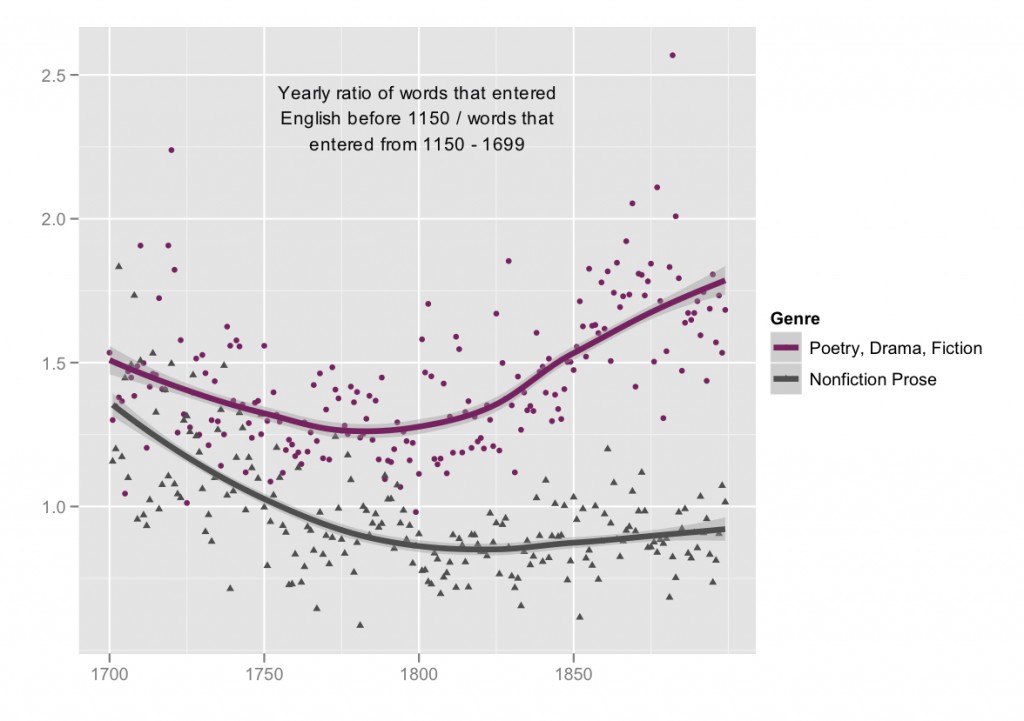

Here, for instance, is one surprising way literary diction differentiated itself from nonfiction prose in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: it began to rely much more heavily on the older part of the lexicon. The graph above is based on a collection of 4,275 (mostly book-length) documents; to make it readable, we’re plotting yearly values rather than individual works. In each year, we have counted the number of words (tokens) that entered English before 1150, and divided it by the number of words that entered the language between 1150 and 1699. (We consider only the most common ten thousand words in the collection, and exclude function words: determiners, prepositions, conjunctions, and pronouns.)

Why do this? and what can it tell us? In English, etymology often has social implications, because the English language was for 200 years (1066-1250) almost exclusively spoken, while French was used for writing. The learned part of the Old English lexicon didn’t survive this period. Instead, when English began to be written again, literate vocabulary was borrowed from French and Latin. As a result, the boundary between words with pre- and post-12th-century origins also tends to be a social distinction between relatively informal and learned/literate language. This was true in the early modern period, and linguists Laly Bar-Ilan and Ruth A. Berman have recently demonstrated that it remains true today.[4]

So the graph above shows that, while all genres of writing tended to adopt a more learned diction in the eighteenth century, poetry, drama, and fiction decisively reversed course in the nineteenth. As a result there was by the end of the nineteenth century a new, sharply marked distinction between literary and nonliterary diction: novels were using the older part of the lexicon at a rate almost double that of nonfiction prose.

The question we are tracing is more commonly described as a tension between “Germanic” and “Latinate” diction. Those terms are used sparingly here, because the underlying social issue has less to do with nationality than with the divergent histories of spoken and written English. Some Latin words, like “street” and “wall,” entered spoken English before the Norman invasion, and it has been more than a millenium since those “Latinate” words seemed recondite to anyone. But it doesn’t make much difference whether we divide the lexicon by chronology or source language: the results are in practice similar. What does make a difference is the exclusion of function words. It is important to exclude them in this context, as Bar-Ilan and Berman explain, because “register variation is essentially a matter of choice” between informal and formal vocabulary.[5] There is no obvious alternative to determiners and prepositions, so whatever they may tell us about authorship or style, they don’t offer reliable clues about social register.

Now, one problem with the graph above is that it lumps together a number of different genres. Apparent changes in literary diction might easily be produced by changing proportions of (say) fiction and poetry in the collection. So it becomes important to break out different genres.

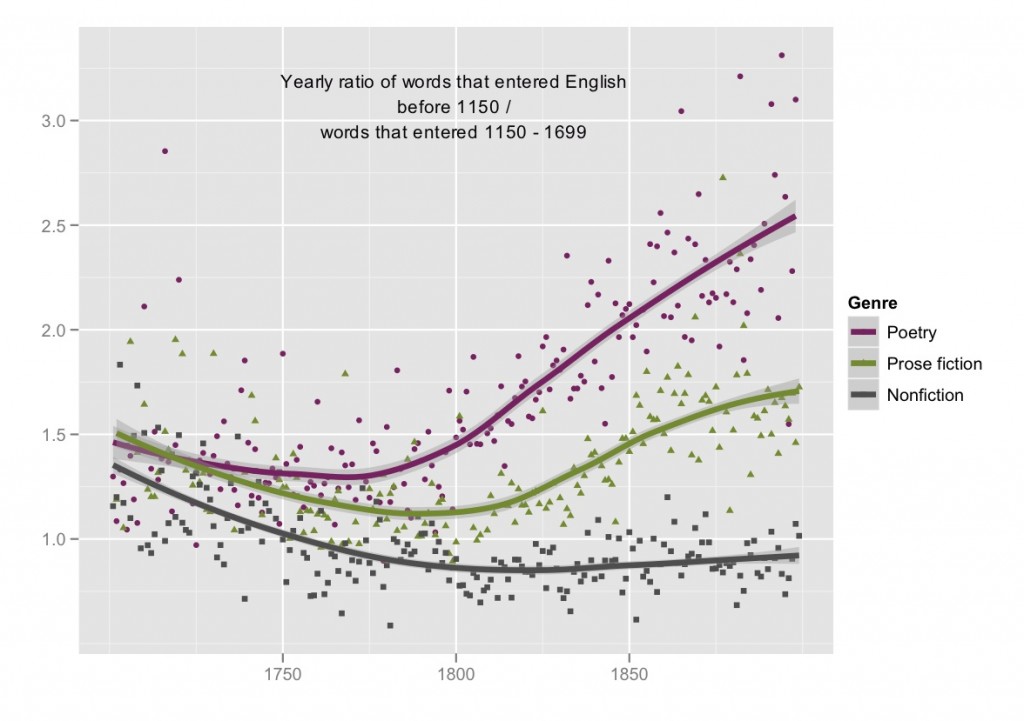

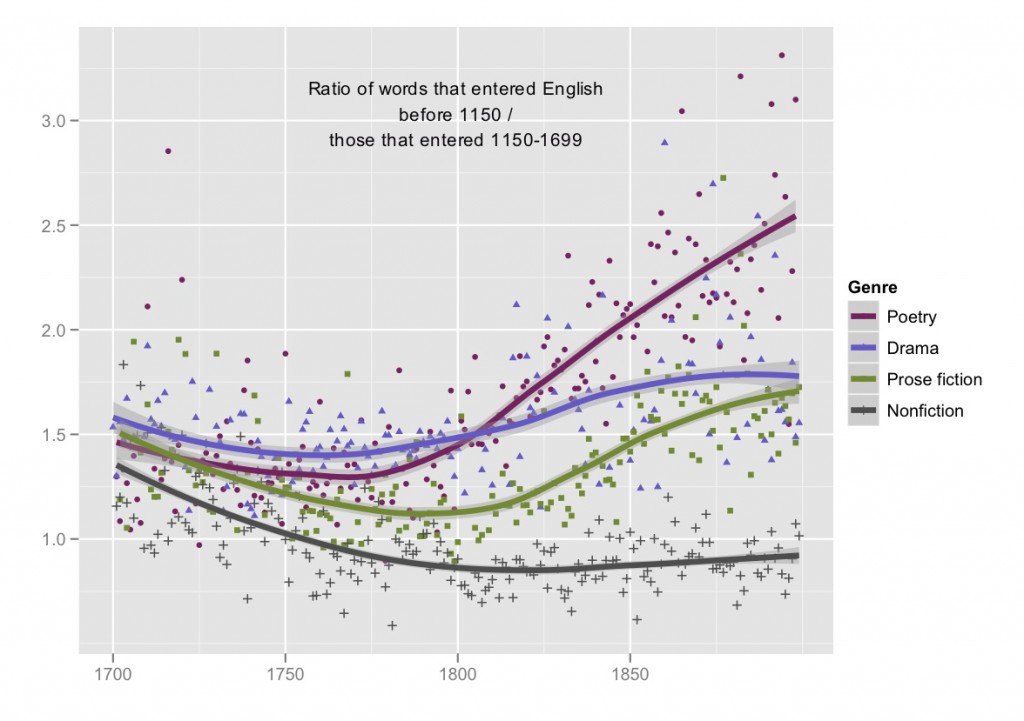

When we do this, the story actually becomes clearer, because poetry (the emblematically literary genre through most of the nineteenth century) diverges from prose fiction just as dramatically as fiction, in turn, diverges from nonfiction. Genres that are difficult to separate in the early eighteenth century break apart in the nineteenth, almost like rays of light passing through a prism.

This of course doesn’t mean that there was no distinction between poetry and prose in the early eighteenth century; writers like Alexander Pope certainly did employ a distinctive poetic diction. But the dimension of diction we’re graphing here (the contrast between older and more recent parts of the lexicon) wasn’t an important differentiating factor in the early eighteenth century. It became an important factor between 1750 and 1900.

We haven’t said anything about drama. Loosely speaking, the diction of dramatic writing follows the same pattern as other literary genres, although the variation is less marked. This makes sense, because dramatic language, although never simply equivalent to conversation, remains loosely bound to a conversational register. The older part of the lexicon is more prominent in speech than in writing (as Bar-Ilan and Berman have shown), so it never declined in drama to the extent that it declined in prose.

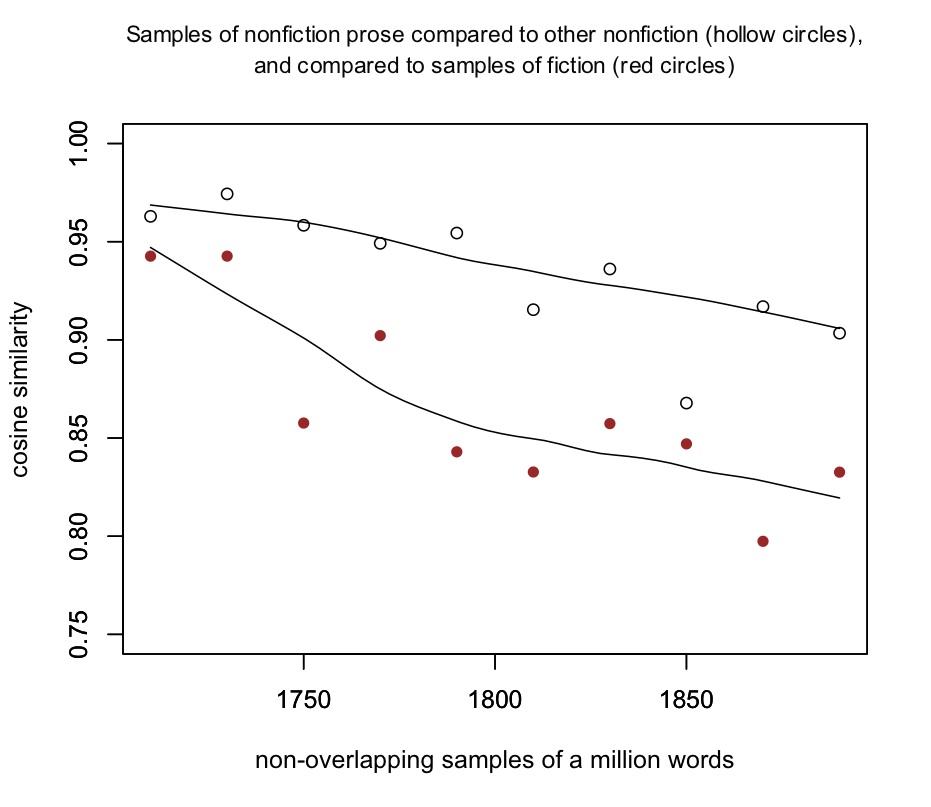

When we initially explored the divergence of genres on The Stone and the Shell, we tried to show that the language of poetry and fiction became less like nonfiction prose, not just according to the particular metric described above (the ratio of pre- and post-twelfth-century words), but generally and absolutely. Establishing this point seemed important at the time — mostly because it simplified the argument. But we have come to the conclusion that it is neither easy, nor all that important, to show that literary genres became less like nonfiction in a general and absolute sense.

It isn’t easy because genres are internally heterogenous. For instance, “nonfiction prose” is a category that becomes less similar to itself over the period studied. It is not difficult to show that fiction became less like nonfiction prose, but it would be fairly difficult to disentangle that change from the internal differentiation of nonfiction genres themselves.

The red circles above represent the similarity of randomly-selected million-word samples of fiction to million-word samples of nonfiction. Similarity is assessed as the cosine similarity of the most common 5,000 words in each pair of samples (my usual list of stopwords excluded).[6] Clearly, fiction is becoming less like nonfiction. But the hollow black circles show that randomly-selected samples of nonfiction also became less similar to each other, probably because the term “nonfiction” covers a steadily broadening range of specialized subject categories. Are the red circles dropping slightly faster than the black ones? Perhaps — but this isn’t exactly a robust result. It’s subtle, and not easily replicable, as Ben Schmidt has demonstrated.

So claims about the absolute similarity of “literary” and “non-literary” diction are difficult to prove. But they’re also a bit moot. Literature as we understand it — a category of writing self-consciously distinguished from nonfiction by fictive and imaginative aims — hardly existed in the early eighteenth century; in fact, authors did everything they could to obscure the boundary between fiction and nonfiction. It’s thus beside the point to prove that the language of fiction was similar to nonfiction in 1720. It’s all you can do to separate the two genres in the first place.

So the interesting task is not to prove that literature in the modern sense did differentiate from nonfiction across the period 1700-1900. We know that already. The interesting question is, What was concretely entailed in the formation of a specialized literary language?

It’s not a full explanation, but it is a useful clue that literary and nonliterary genres acquired a radically different relationship to lexical history. By the end of the nineteenth century, poets had developed a specialized diction, inherited largely from the period before Middle English was a written language. Poems were using those words at nearly three times the rate of nonfiction books — a differentiation that had not existed at all in 1700. To be sure, changes in nonfiction are responsible for part of this divergence: scientific discourse no doubt made nonfiction slightly more Latinate. But poetry changed even more than nonfiction did, and it did so in parallel with fiction and drama. (The trajectories of different genres are “parallel” not just in the sense that these changes happened at roughly the same time, but — as we explain below — in the sense that the changes tended to affect the same specific words in different genres.) Because the effect of these shifts was often to make writing more accessible, critics have not ordinarily perceived this as a process of specialization. But by revealing the magnitude of change and the strong parallel between literary genres, text mining makes clear that this shift amounted to the formation of a specialized literary language.

How should we understand the logic of this specialization? An important clue can be drawn from the way the curves bend. Prose fiction, poetry, and drama become more Latinate in parallel with nonfiction through most of the eighteenth century, reversing course slightly before or after the year 1800. The reversal coincides with a series of well-known debates about English diction. The best-known of these is no doubt the controversy stirred up by Lyrical Ballads, but Robin Valenza has shown that Wordsworth’s questions about poetic diction were only the culmination of a longer debate about language. Eighteenth-century writers had become uneasy about specialized and learned diction. They could be persuaded to embrace it as a necessary correlate to refinement of thought: Samuel Johnson made that argument very effectively. But writers longed at the same time for a common, public language. Valenza argues that Romantic poets resolved this dilemma by offering poetry as a neatly paradoxical solution: “a practice whose specialized role was the creation of common language and universal experience.”[7] The trajectory of poetic diction in the nineteenth century tends to confirm Valenza’s account of this paradox. In a sense, poetry became more specialized than it had been before: its diction became (at least in certain ways) more remote from prose. But it specialized in the direction of old words that would appear plain, common, and universal.

An alternate explanation for this phenomenon has recently been offered by Ryan Heuser and Long Le-Khac, writing in the Stanford Literary Lab pamphlet series.[8] Heuser and Le-Khac trace two strongly correlated changes in the diction of the nineteenth-century novel: a decline in the prominence of “abstract values” and an increase in the prominence of concrete words, including action verbs, body parts, colors, and numbers. They link these transformations both to the rise of narrative realism (showing rather than telling), and to a transformation of “social space” that “made it more and more difficult to maintain the idea of a knowable community” organized by a single set of values.[9]

This is work of groundbreaking importance, both for the nineteenth-century novel, and for the development of quantitative methodology in literary studies. However, precisely because this is such an important result, critics need to have a vigorous debate about its significance. The phenomenon Heuser and Le-Khac are describing overlaps in great part with the one we are describing here. As they acknowledge, their “abstract values” are almost all French or Latinate words (“integrity, modesty, sensibility, reason”). Their concrete words or “hard seeds,” by contrast, are very largely drawn from the pre-1150 part of the English lexicon (“come, go, finger, chin, red, white”). So the shift they describe in the 19th-century novel is (not identical to, but) largely consubstantial with the second, rising half of the fiction curve in the graphs presented above. However, we are now in a position to see that this curve was rising in the nineteenth century only because it had recently reversed direction. The relative scarcity of simple action verbs in early-nineteenth-century writing, for instance, was a recent development.

In this context, the transformation of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century diction may not look like a story about a steady transition from traditional values to a modern, fragmented society. That is why we propose to interpret diction, not as direct evidence about a transformation of community, but as evidence about competing ideals of literary refinement, which reveals social history only indirectly, through the mediation of those ideals.

However, this isn’t to deny the significance of the history Heuser and Le-Khac have traced. When we look at the history of the nineteenth-century novel, we don’t have to decide whether we are observing the rise of realism or the rise of a new model of literary refinement. We are seeing both things at once, and Heuser and Le-Khac can help us understand how those two broad changes are related.

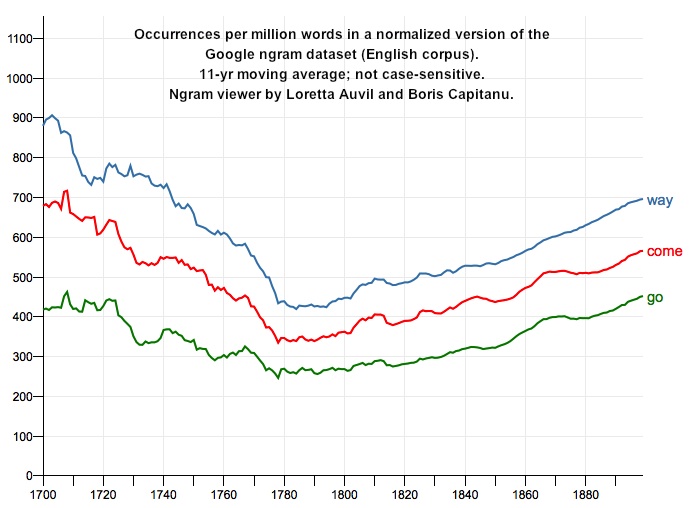

Moreover, they are absolutely right to emphasize that the mere correlation of word frequencies can be a powerful tool for mapping trends in literary history. As the graph of “way,” “come,” and “go” above suggests, the frequencies of conceptually-related words often track each other across long periods of time in an amazingly reliable way. So one way to flesh out the significance of a literary trend is just to ask what particular kinds of language tend to correlate with it.

For instance, it would be hasty to interpret changes in diction without asking which words in particular were affected. Although pre-twelfth-century words became (in the aggregate) more common in nineteenth-century literature, the etymological dimension of this trend might only be a symptom of some other underlying issue. One way to tease out the underlying issue is to search for the individual words whose yearly frequencies correlate most closely with the yearly variation of the pre/post-1150 ratio. That could reveal thematic or social changes associated with the trend, even if they had no inherent connection to etymology.

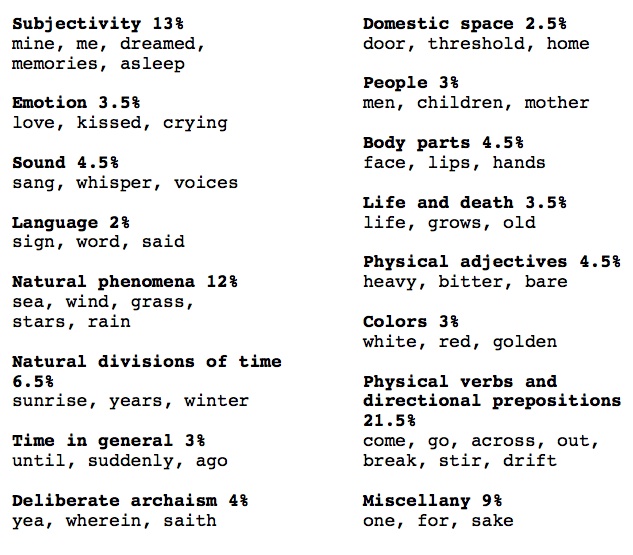

For the purpose of this brief essay, we focus on poetry, since poetry seems to present the differentiation of literary diction in its most extreme form. To give a snapshot picture of the changes in poetic diction, we have selected the 200 words that correlate most closely with the rising pre/post-1150 ratio from 1760 to 1899. (We narrow the temporal window to the the rising half of the curve, because the decline that preceded it might have been governed by a different social logic.) This produces a list of words that is thematically very coherent, and to make the coherence visible we have organized the list into salient categories.

This list overlaps in many ways with the “hard” or concrete diction traced by Heuser and Le-Khac (body parts, colors, physical verbs). But “dreamed,” “love,” and “word” are not exactly concrete. Admittedly, we’re looking at poetry here, whereas Heuser and Le-Khac are looking at fiction. But there’s a high degree of overlap between the two processes of change; if you measure words’ correlation with the pre/post-1150 ratio in poetry, and also in fiction, and then compare the two lists of words, it turns out that they’re sorted in much the same way. (Technically, there’s a meta-correlation-coefficient of o.54 between the two lists of correlation coefficients — which, for ten thousand data points (words), is a very significant degree of association.)

This list overlaps in many ways with the “hard” or concrete diction traced by Heuser and Le-Khac (body parts, colors, physical verbs). But “dreamed,” “love,” and “word” are not exactly concrete. Admittedly, we’re looking at poetry here, whereas Heuser and Le-Khac are looking at fiction. But there’s a high degree of overlap between the two processes of change; if you measure words’ correlation with the pre/post-1150 ratio in poetry, and also in fiction, and then compare the two lists of words, it turns out that they’re sorted in much the same way. (Technically, there’s a meta-correlation-coefficient of o.54 between the two lists of correlation coefficients — which, for ten thousand data points (words), is a very significant degree of association.)

In short, this list, taken as a whole, confirms our conjecture that literary diction was specializing in elemental aspects of experience. But it also fleshes out just what counted as elemental in nineteenth-century Britain and America. Subjectivity, domestic space, the body, and physical perception lead the list — especially physical perception of large natural phenomena like sunrise and the sea.

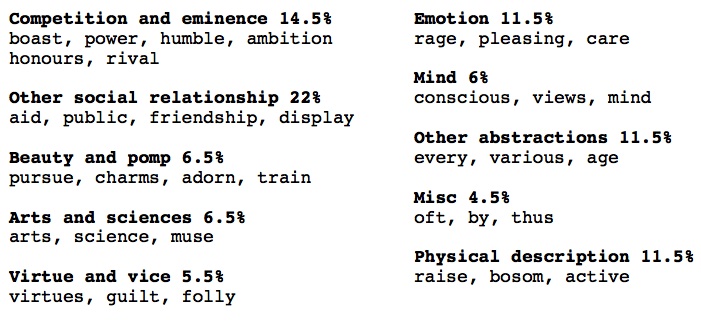

To refresh our sense of what was being displaced by this model of literary refinement, we can simply look at the 200 words that have the strongest inverse correlation with the pre/post-1150 trend. These are words, in other words, that tended to decline as that ratio rose (although we find them not by looking for decline as such but by looking for inverse correlation with the yearly variation of the ratio).

The most striking difference is that this list is far more social. About half of the negative correlates describe some kind of social relationship — a category of experience that was almost entirely missing in the list of positive correlates. It is particularly worth noting a strong emphasis on competition and display — “boast, ambition, grandeur, pomp, refined, taste.” The strong presence of that theme in this list perhaps helps us recognize how strongly it was disavowed in later-nineteenth-century poetic diction. Nineteenth-century poetry still of course made a claim to cultural eminence, but it did so by presenting itself as a mode of experience so primitive, homely, and private that social competition became moot. Aesthetic distinction was so different from other forms of status as to constitute its own autonomous sphere.

The most striking difference is that this list is far more social. About half of the negative correlates describe some kind of social relationship — a category of experience that was almost entirely missing in the list of positive correlates. It is particularly worth noting a strong emphasis on competition and display — “boast, ambition, grandeur, pomp, refined, taste.” The strong presence of that theme in this list perhaps helps us recognize how strongly it was disavowed in later-nineteenth-century poetic diction. Nineteenth-century poetry still of course made a claim to cultural eminence, but it did so by presenting itself as a mode of experience so primitive, homely, and private that social competition became moot. Aesthetic distinction was so different from other forms of status as to constitute its own autonomous sphere.

This is not an obviously Latinate list of words, and it is unlikely that poets who drew on words from either list were often conscious of the etymological dimension of their rhetoric. But it happens to be the case that only 34 of 200 words in the first list have a date of entry after 1149, whereas 171 of the words in the second list do. While it’s certainly possible to point to writers who did use words with a conscious awareness of their origins, I suspect the etymological coloration of these lists is on the whole accidental. It may be a by-product of the fact that English vocabulary for social organization and public distinction is largely borrowed from French and Latin (for obvious reasons associated with the Norman Conquest), whereas private, domestic, and bodily experiences are covered by an older set of words.

This is a blog post in the process of becoming an essay; it aims to offer provocation rather than conclusive proof. Much more could be said, especially because different genres changed in ways that were parallel, but not identical. But these questions are too large to be resolved by a single article anyway. What really matters is not the particular thesis advanced here (that literary diction specialized by disavowing learning and social competition), but an emergent question of fundamental significance for literary study — a question about the history of literary language and of literature itself. It appears that a number of different scholars have been converging on this question and illuminating different parts of it; in the process, we are beginning to understand how quantitative methods can make a contribution to central themes of literary scholarship. For one thing, quantitative analysis allows us to back up far enough to see how a series of existing debates (about realism, cultural distinction, and poetic diction, for instance) might fit together as interlocking pieces of a single picture.

So this is a collective enterprise, and even the small part of the project described above has been collective. The by-line of this essay acknowledges Jordan Sellers, who designed the nineteenth-century part of the collection that Ted Underwood is describing in this article. (The eighteenth-century part was mostly contributed by ECCO-TCP.) But this argument has evolved in public, and we should almost give by-line credit to many other people as well. Harriett Green at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign library helped us obtain many of the sources used here. Responses from Natalie Houston and Katherine Harris convinced us to enlarge the collection, and the Brown Women Writers Project generously allowed us to borrow some of their texts. Critiques from Ben Schmidt, Scott Weingart, John Theibault, Ryan Cordell, and others at The Stone and the Shell — as well as Mark Liberman and Nick Lamb at Language Log — fundamentally transformed this project, and steered it away from dead ends. Conversation with Ryan Heuser and Matt Jockers shaped our thinking about the uses of correlation in literary study; Loretta Auvil and Boris Capitanu built a correlation engine and ngram viewer that we use constantly. Research on the project was supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and we could not have undertaken it without the guidance of John Unsworth. Since the project has been so collective, it is worth underlining that the standard disclaimer does still apply: interpretive mistakes and controversial assertions in this article can be safely blamed on Underwood.

Supporting data and code

Most of the visualizations presented in this article are based on a collection of 4,275 documents; you can download a tabular summary of the metadata for the whole collection. We don’t have the right to redistribute all of the documents, but the collection can be reconstructed from three sources — eighteenth-century documents from ECCO-TCP, documents in the period 1700-1850 from the Brown Women Writers Project, and a collection of nineteenth-century books selected by Jordan Sellers, available as a .zip file (350MB). The 19c files are based on optically scanned text, but we corrected the OCR with a Python script that considered the probability of specific character substitutions and word sequences in a 19c context. Word-by-word recall is now better than 95%, and precision (which matters more for the analysis conducted here) is better than 98%. Error levels do vary across the time axis, since the eighteenth-century texts are mostly transcribed by hand. But it is difficult to imagine how that variation would produce effects on the scale revealed here — let alone different effects in different genres.

When doing generic comparisons of poetry and prose, it is important to generate versions of the poetry files where prose introductions, notes, and lists of subscribers are stripped away, leaving only the verse. Otherwise, late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century books of poetry are often in practice mostly prose. We’ve done this in a quick and dirty way, relying on the density of line-initial capitalization to identify verse, and other lexical cues to separate “lists of subscribers” from the verse. Obviously a capitalization-based strategy wouldn’t work to identify verse by e.e. cummings, but it works acceptably in 18th- and 19th-century contexts. Ideally, dramatic texts would be cleaned in a similar way, but that might have to be a manual process, and we haven’t yet undertaken it. You can convert the collection to a sparse table of word frequencies using any tokenizer, although ideally the tokenizer should be aware of historical changes in word segmentation (today / to-day / to day).

Underwood analysed the collection in R, using the RMySQL package to query word-frequency tables in an underlying MySQL database. The R scripts are available on github; visualizations were produced with ggplot2.

Etymologies were extracted from dictionary.com using a web-scraper that crawled links where necessary to identify the date-of-entry of the underlying lemma. The full list is available here; dates earlier than “900” mark proper nouns, abbreviations, or stopwords — all of these were excluded from the analysis.

Earlier versions of this work were posted at The Stone and the Shell on February 26, 2012, March 2, 2012, and March 9, 2012. This version was substantially revised for the Journal of Digital Humanities to respond to comments and recently-published scholarship.

- [1]Trevor Ross, The Making of the English Literary Canon (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1998). For the underlying social assumptions Ross is making, see Pierre Bourdieu, “The Field of Cultural Production, or: The Economic World Reversed,” The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature, ed. Randal Johnson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 29-73.↩

- [2]William Wordsworth, Lyrical Ballads, with Pastoral and Other Poems, 4th ed., vol. 1 (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1805), vii.↩

- [3]D. H. Lawrence, “Why the Novel Matters,” Study of Thomas Hardy and Other Essays, ed. Bruce Steele (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 191-99.↩

- [4]Laly Bar-Ilan and Ruth A. Berman, “Developing Register Differentiation: the Latinate-Germanic Divide in English,” Linguistics 45 (2007): 1-35.↩

- [5]Ibid., 15.↩

- [6]There are valid reasons to choose different metrics of similarity between corpora. For a full discussion, see Adam Kilgarriff, “Comparing Corpora,” International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 6.1 (2001): 97-133.↩

- [7]Robin Valenza, Literature, Language, and the Rise of the Intellectual Disciplines in Britain, 1680-1820 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 142.↩

- [8]Ryan Heuser and Long Le-Khac, A Quantitative Literary History of 2,958 Nineteenth-Century British Novels: The Semantic Cohort Method, Pamphlet 4, The Stanford Literary Lab, May 2012. See also Ryan Heuser and Long Le-Khac, “Learning to Read Data: Bringing out the Humanistic in the Digital Humanities,” Victorian Studies 54.1 (2011): 79-86.↩

- [9]Heuser and Le-Khac, Quantitative Literary History, 36.↩