The Impact of Social Media on the Dissemination of Research: Results of an Experiment

Melissa Terras

In September 2011 I returned to work after a year on maternity leave. Many things needed sorting out, not least my digital presence at my home institution, which had switched to a content management system that seamlessly linked to University College London’s open-access repository, “Discovery.” The idea was we should upload open-access versions of all our previously published research, and link to it from our home pages, to aid in dissemination.

There is no doubt that this type of administrative task is tedious. To break up the monotony of digging out the last previous version prior to publication of my 26 journal papers (we put up a last-but-one copy to get around copyright issues with journals) I decided to blog the process. I wrote a post about each paper, or each research project that had spawned papers. I wanted to tell the stories behind the research — the things that don’t get into the published versions. I also set about methodically tweeting about these research papers, as they went live, going through my back catalogue in reverse chronological order.

What became clear to me very quickly was the correlation between talking about my research online and the spike in downloads of my papers from our institutional repository. A game that had spurred me to carry out an administrative task was actually disseminating my research quite effectively. So this, in turn, became the focus of the blog posts that are featured here.

The first, “What Happens When You Tweet an Open-Access Paper” discusses the correlation between talking about an individual paper online, and seeing its downloads increase. The second, “Is Blogging and Tweeting About Research Papers Worth It? The Verdict” discusses the overall effect of this process on all my papers, highlighting what I think the benefits of open access are. In the final post, “When Was the Last Time You Asked How Your Published Research Was Doing?” I talk about the link between publishers and open access, and how little we know about how often our research is accessed once it is published.

More than 20,000 people have now read these three online posts. It is evident to me that academics need to work on their digital presence to aid in the dissemination of their research, to both their subject peers and the wider community. These blog posts provide the evidence to prove this.

What Happens When You Tweet an Open-Access Paper

So a few weeks ago, I tweeted and posted about this paper:

Melissa Terras, “Digital Curiosities: Resource Creation Via Amateur Digitisation,” Literary and Linguistic Computing, 25.4 (2009): 425 – 438. Available in PDF.

I thought it worth revisiting the results of this. Is it worth me digging out the full text, running the gamut with the UCL repository, and trying to spend the time putting my previous research online? Is open access a gamble that pays, and if so, in what way?

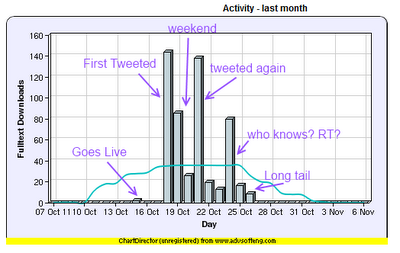

Prior to me blogging and tweeting about the paper, it was downloaded twice (not by me). The day I tweeted and blogged it, it immediately got 140 downloads. This was on a Friday; on the Saturday and Sunday it got downloaded, but by fewer people. On Monday it was retweeted and the paper received a further 140 or so downloads. I have no idea what happened on the 24th of October — someone must have linked to it? Posted it on a blog? Then there were a further 80 downloads. Then the traditional long tail, then it all goes quiet.

All in all, it’s been downloaded 535 times since it went live, from all over the world: USA (163), UK (107), Germany (14), Australia (10), Canada (10), and the long tail of beyond: Belgium, France, Ireland, Netherlands, Japan, Spain, Greece, Italy, South Africa, Mexico, Switzerland, Finland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Portugal, Europe, United Arab Emirates, “unknown”.

Worth it, then? Well there are a few things to say about this.

- I have no idea how many times it is read, accessed, or downloaded in the journal itself. So seeing this — 500 reads in a week! — makes me think, “wow, people are reading something I have written!”

- It must be all relative, surely. Is 500 full downloads good? Who can tell? All I can say is that it puts it into the top ten — maybe top five — papers downloaded from the UCL repository last month (I won’t know until someone updates the webpage with last months statistics).

- If I tell you that the most accessed item from our department ever in the UCL repository, which was put in there five years ago, has had 1,000 full text downloads, then 500 downloads in a week isn’t shabby. They didn’t blog or tweet it, it’s just sitting there.

- There is a close correlation between when I tweet the paper and downloads.

- There can be a compulsion to start to pay attention to statistics. Man, it gets addictive. But is this where we want to be headed: academia as X-factor?

Ergo, if you want people to read your papers, make them open access, and let the community know (via blogs, twitter, etc.) where to get them. Not rocket science. But worth spending time doing. Just don’t develop a stats habit.

—

The updated UCL statistics page for downloads shows that “Digital Curiosities” was the fifth most downloaded paper in the UCL repository in October 2011. Yeah, I’m up there with fat tax, seaworthiness, preventative nutrition, and the peri-urban(?) interface. The Digital Curation Manager at UCL, Martin Moyle, has been in touch to confirm that 6,486 of the 224,575 papers in the repository have downloadable full text attached.

Is Blogging and Tweeting About Research Papers Worth It? The Verdict

Guess When I Tweeted My Papers? Top Ten Downloaded Papers From My Department in the Last Year, Seven of Which Include Me in the Author List

In October 2011, I began a project to make all of my 26 articles published in refereed journals available via UCL’s Open Access Repository, Discovery. I decided that as well as putting them in the institutional repository, I would write a blog post about each research project, and tweet a link to download the paper. Would this affect how much my research was read, known, discussed, distributed?

I wrote about the stories behind the research papers — from becoming so immersed in developing 3D that you start walking into things in real life, to nearly barfing over the front row of an audience’s shoes whilst giving a keynote, to passive aggressive notes from an archaeological dig that take on a digital life of their own. I gave a run down, in roughly reverse chronological order, of the twelve or so projects I’ve been involved in over the past decade that resulted in published journal papers. Along the way, I wrote a little bit about the difficulties of getting stuff into the institutional repository in the first place, but the thing that really flew was my post on what happens when you blog and tweet a journal paper, showing (proving?) the link between blogging and tweeting and the fact that people will download your research if you tell them about it.

So what are my conclusions about this whole experiment?

Some rough stats, first of all. Most of my papers, before I blogged and tweeted them, had one to two downloads, even if they had been in the repository for months (or years, in some cases). Upon blogging and tweeting, within 24 hours, there were on average 70 downloads of my papers. Seventy. Now, this might not be internet meme status, but that’s a huge leap in interest. Most of the downloads followed the trajectory I described with the downloads of “Digital Curiosities,” in that there would be a peak of interest, then a long tail after. I believe that the first spike of interest from people clicking the link that flies by them on twitter (which was sometimes retweeted) is then replaced by a gradual trickle of visitors from postings on other blogs, and the fact that the very blog posts about the papers make them more findable when the subject is googled. People read the blog posts — I have about 2,000 visitors to my blog a month, 70% new, with an average time on the site of one minute and five seconds. People come here, tend to read what I have written, and seem to be clicking and downloading my research papers.

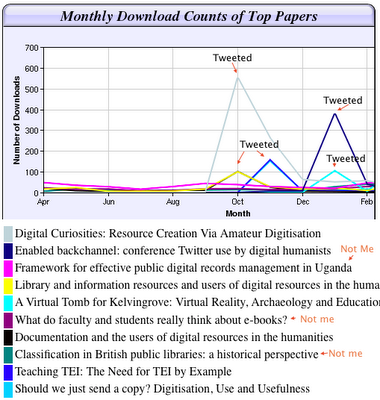

The image above shows the top ten papers downloaded from my entire department over the last year. There were a total of 6,172 downloads from our department (UCL Department of Information Studies is one of the leading iSchools in the UK). Look at the spikes. That’s where I blog and tweet about my research. I’m not the only person producing research in my department (I think there are eighteen current staff members and a further twenty or so who have moved on but still have items in the institutional repository) but I’m the only person who has gone the whole hog on promoting their research like this. You will see that seven out of ten of the most downloaded papers from my Department in the last calendar year have me in the author list. As a clue, I don’t know anything about Uganda, e-books, or classification in public libraries. In the last calendar year 27 out of the top 50 downloads in our department feature me (as a rough guide, I get about 1/3 of the entire downloads for my department). My stuff isn’t better than my colleagues’ work. They’re all doing wonderful things! But I’m just the only one actively promoting access to my research papers. If you tell people about your research, they look at it. Your research will get looked at more than papers which are not promoted via social media.

Some obvious points and conclusions. Don’t tweet things at midnight, you’ll get half the click throughs you get during the day when people are online. Don’t tweet important things on a Friday, especially not late — people do take weekends and you can see a clear drop off in downloads when the weekend rolls around and your paper falls a bit flat, as you sent it on its way on social media at the wrong time. The best time is between 11am and 5pm GMT, Monday to Thursday in a working week. I have the stats here somewhere to prove it. I won’t write it up, though, as it’s pretty predictable. It is important to note that just putting links on twitter isn’t enough, you have to time it right. The Discovery twitter account regularly posts an automated list of the really interesting things people have been looking at … at 10pm on a Friday night. I only know as I’m regularly sad enough to still be on twitter at that time, but I suspect if they tweeted the papers through the day during the working week … well, you guess what would happen.

The paper that really flew — “Digital Curiosities” — has now been downloaded over a thousand times in the past year. It was the 16th most downloaded paper from our entire institutional repository in the final quarter of 2011, and the third most downloaded paper in UCL’s entire Arts Faculty in the past year. It’s all relative really — what does this really mean? Well, I can tell you that this paper was the most downloaded paper in 2011 in Literary and Linguistic Computing (LLC) Journal, where it was published (and where it lives behind a paywall apart from being available free from Discovery). LLC is the most prestigious journal in the discipline I operate in, Digital Humanities. The entire download count for this paper from LLC itself, which made it top paper last year? 376 full text downloads. There have been almost three times that number of downloads from our institutional repository. What does this mean? What can we extrapolate from this? I think it’s fair to say that it’s a really good thing to make your work open access. More people will read it than if it is behind a paywall. Even if it is the most downloaded paper from a journal in your field, open access makes it even more accessed.

However, I might just have written a nice paper that caught peoples’ interest; there are, after all, no controls to this, are there? No controls! How can we tell if papers would fly without this type of exposure? Well. Erm. I might have not tweeted one or two papers to see the difference between tweeting and blogging about papers and not doing so. Take the LAIRAH (Log Analysis of Internet Resources in the Arts and Humanities) project, which I wrote about here. We actually published four papers from this research. I tweeted and promoted three of them actively. One I didn’t mention to you. Here are the download counts. Guess which one I didn’t circulate?

- “Library and information resources and users of digital resources in the humanities“: 297 downloads.

- “Documentation and the users of digital resources in the humanities“: 209 downloads.

- “If You Build It Will They Come? The LAIRAH Study: Quantifying the Use of Online Resources in the Arts and Humanities through Statistical Analysis of User Log Data“: 142 downloads.

- “The Master Builders: LAIRAH Research on Good Practice in the Construction of Digital Humanities Projects“: 12 downloads.

The papers that were tweeted and blogged had at least more than 11 times the number of downloads than their sibling paper which was left to its own devices in the institutional repository. Q.E.D., my friends. Q.E.D.

I can’t know if the downloaded papers are read though, can I? The only way to do so is to enter the murky world of citation analysis. The trouble with this is the proof of the pudding will come to light in a few years time — if someone reads something of mine now and decides to cite it, it’s going to take one or even two years (or more) for it to appear in my citation list. So, I’ll be keeping an eye on things, not too seriously as we all know things like H-index are problematic. Just for the record, at time of writing, I have 218 citations, according to Google Scholar. My H-index is 8, and my i10 index is 5, which is ok for a relatively young Humanities scholar (I’m still technically an Early Career Researcher for another year, as defined by the UK funding councils). “Digital Curiosities” only has three published citations to date. Three published citations. Remember, it’s been downloaded over 1,300 times, between LLC and our repository. Will this citation count grow? Will I be able to demonstrate, over the next few years, that retweeting leads to citation? Will I be able to tell how people came across my research? We’ll see. Don’t worry, I’ll blog it if I have anything to say on this.

I also know nothing about how many times my other papers are downloaded from the websites of published journals, or consulted in print in the library. The latter, no one can really say much about — but the former? It seems strange to me that we write articles (without being paid) and we get them published by people who make a profit on them, yet we don’t even know — usually — how many downloads they are getting from the journals themselves. The only reason I know about the LLC statistics is because I am good friends with the editor. So, there are obvious advantages to being able to monitor my own downloads from my institutional repository. It’s been a surprise to me to see what papers of mine are of interest to others. (Should that drive my research direction, though?)

The final point to make is that people don’t just follow me or read my blog to download my research papers. This has only been part of what I do online — I have more than 2,000 followers on twitter now and it has taken me over three years of regular engagement — hanging out and chatting, pointing to interesting stuff, repointing to interesting stuff, asking questions, answering questions, getting stroppy, sending supportive comments, etc. — to build up an “audience” (I’d actually call a lot of you friends!). If all I was doing was pumping out links to my published stuff, would you still be reading this? Would you have read this? Would you keep reading? My blog is similar: sure, I’ve talked about my research, but I also post a variety of other content, some silly, some serious, as part of my academic work. I suspect this little experiment only worked as I already had a “digital presence,” whatever that may mean. All the numbers, the statistics. Those clicks were made by real people.

So that would be my conclusion, really. If you want people to find and read your research, build up a digital presence in your discipline, and use it to promote your work when you have something interesting to share. It’s pretty darn obvious, really:

If (social media interaction is often) then (open access + social media = increased downloads).

What next? From now on, I will definitely post anything I publish straight into our institutional repository, and blog and tweet it straight away. After all, the time it takes to undertake research, and write research papers, and see them through to publication is large; the time it takes to blog or tweet about them is negligible. This has been a retrospective journey for me, through my past research, at a time when I came back from a period of leave. It’s been fun to get my act together like this — in general I needed to sort out my online systems at UCL, so it gave me some impetus to do so. But it has shown me that making your research available puts it out there — and as soon as I have something new to show you, you’ll be the first to know.

When Was the Last Time You Asked How Your Published Research Was Doing?

Whilst writing up my thoughts about whether blogging and tweeting about academic research papers was “worth it,” the one thing that I found really problematic was the following:

I also know nothing about how many times my other papers are downloaded from the websites of published journals, or consulted in print in the Library. The latter, no one can really say much about — but the former? It seems strange to me that we write articles (without being paid) and we get them published by people who make a profit on them, yet we don’t even know — usually — how many downloads they are getting from the journals themselves.

That’s true enough, I thought. But whose fault is it that I don’t know about access statistics for journals I have published in? Have I ever asked for the access statistics for how many times my papers have been downloaded from the journals they are published in? Has anyone?

So, Reader, I asked for some facts and figures regarding the circulation of journals and the download statistics of my papers.

I have to say that the journals were really very helpful, and forthcoming, if surprised. “I imagine the publishers would be happy to tell an author the cumulative downloads for their papers … So far as I know, you are the first author ever to ask … certainly the first to ask me,” said David Bawden, editor of the Journal of Documentation (JDoc). Jonas Söderholm, editor of HumanIT, highlighted some of the issues journals will face if people start asking this kind of question, saying:

A reasonable request and we would gladly assist you. Unfortunately we do not have direct access to server logs as our web site is hosted as part of the larger University of Borås web. We will take your request as a good excuse to check into the matter though, and also review our general policy on log data.

Most journals got back to me by return of email, telling me immediately what they knew and were very aware of the limitations of their reporting mechanisms, for example whether or not the figures excluded robot activity, the fact that how long the user stays on the website is not known so accidental click-throughs are undetermined, etc. Such caveats were explained in detail. Emerald, the publishers of JDoc and Aslib Proceedings, were not comfortable with giving me access to wider statistics about their general readership numbers, given this could be commercially sensitive information, which is understandable; they were very happy to give me the statistics relating to my own papers, though.

The only journal not to get back to me was LLC , published by Oxford University Press (the editor replied to say he was not sure he had access to these statistics, but would ask). This is ironic, given I’m on the editorial board. I’ll press further, and take it to our summer steering-group meeting.

I suspect that the actual statistics involved are only really very interesting to myself. I had originally planned to make comparisons with the amount of downloads from UCL Discovery (open access is better, folks! etc.), but I think the picture is foggier than that. What this exercise does do is highlight the type of information that, as authors, we don’t normally hear about, which can be actually quite interesting for us, as well as stressing the complex relationship between open access and paywalled publications. Here are some details:

- One of my papers published in JDoc, “Enabled backchannel: conference Twitter use by digital humanists,”[1] was downloaded 804 times from the JDoc website during 2011, and was number 16 in the download popularity list that year. The total number of paper downloads from JDoc as a whole during that year was 123,228. Isn’t that interesting to know? I have a top twenty paper in a really good journal in my discipline! Who knew? It has now been downloaded 1,114 times from their website. In comparison, there have been 531 total downloads of that paper from UCL Discovery in the past six months. But the time frame for comparison of downloads with the open-access copy from Discovery isn’t the same, so comparing is problematic — and there are more downloads from the subscription journal than from our open-access repository. Still, it shows a healthy amount of downloads, so I’m happy with that.

- The Art Libraries Journal, only available in print, not online, were quick to tell me that the journal is distributed to 550 members: 200 going abroad to Libraries/Institutions, 150 sent to UK Personal members, and 200 going to UK Libraries/Institutions. My paper published there, “Should we just send a copy? Digitisation, Use and Usefulness,”[2] has had 205 downloads in the last six months from UCL Discovery, so I perceive that as a really good additional advert for open access: the print circulation is fairly limited, but the open-access copy is available to all who want it.

- My paper in the open-access International Journal of Digital Curation, “Grand Theft Archive: a quantitative analysis of the current state of computer game preservation,”[3] was downloaded 903 times in 2009 out of the 53,261 times the full text of a paper was accessed. (The average was 476, with standard deviation 307). In 2010 the paper accounted for 919 out of the 120,126 times the full text of a paper was accessed. (The average was 938, with standard deviation 1,045.) That compares to only 85 downloads from the UCL repository, but hey, it’s freely available online anyway, without having to revert to an open-access copy in an institutional repository. It might be worth drawing from this that copies of papers in institutional archives are only really used when the paper isn’t available anywhere else, but you would hope that would be obvious, no?

- Internet Archaeology has an online page with their download statistics readily available (how I wish all journals would do this). The journal gets around 6,200 page requests per day. But since article size varies widely, with some split into hundreds of separate HTML pages, it is difficult to know how meaningful this is. I was sent a spreadsheet of the statistics from my paper published there, “A Virtual Tomb for Kelvingrove: Virtual Reality, Archaeology and Education,”[4] which suggests that there have been 2,083 downloads of the PDF version of the paper from behind the paywall since 2001 (but some may be missing due to the way the reporting mechanism is set up) with none in the past year (compared to 276 downloads of this from UCL Discovery in the past six months, so many more from our institutional repository comparing like periods). The HTML version of the table of contents has been consulted 16,282 times since 2001 (this is freely available to all comers) but there have been 67,525 views of all files in the directory since then — but since the paper is comprised of hundreds of individual files, it is difficult to ascertain readership. Judith Winters, the editor of Internet Archaeology, notes “It is curious that when the journal went open access for about 2 weeks towards the end of last year, the counts did increase but not dramatically so” — so when a non-open-access journal throws open its doors for a limited time (Internet Archaeology did this to mark Open Access Week last year) it is not like access figures go wild. That’s really interesting, in itself.

It has been fascinating, for me, to see the (mostly positive) reactions publishers have to being approached about this — and surprising that not more people have actually asked publishers about these statistics. We are giving away our scholarship to publishers, in most cases; shouldn’t we get to know how it fares in the wide, wide world? As citation counts, and H-indexes, and “impact” become increasingly important to external funding councils and internal promotion procedures within universities, why would journal publishers not make this information available to authors?

Will you need this type of information for the next grant proposal, or internal promotion, you chase? Why would you not be interested in how your research flies? But journal publishers will only start providing authors with this kind of information routinely if enough scholars start to ask about it, and it becomes part of the mechanics of publishing research — particularly when publishing research online.

So if you have published in a print journal which has an online presence, or in an online journal, drop them an email to ask politely how your downloads are going. Do it. Do it now. Ask them. Ask them!

Originally published by Melissa Terras on November 7, 2011, April 3, 2012, and May 16, 2012. Revised with new introduction for Journal of Digital Humanities September 2012.

- [1]Claire Ross, et al. “Enabled Backchannel: Conference Twitter Use by Digital Humanists,” Journal of Documentation 67.2 (2011): 214 – 237.↩

- [2]Melissa Terras, “Should we just send a copy? Digitisation, Use and Usefulness,” Art Libraries Journal 35.1 (2010).↩

- [3]Paul Gooding and Melissa Terras, “Grand Theft Archive: a quantitative analysis of the current state of computer game preservation,” International Journal of Digital Curation 3.2 (2008).↩

- [4]Melissa Terras, “A Virtual Tomb for Kelvingrove: Virtual Reality, Archaeology and Education,” Internet Archaeology 7 (1999).↩