QRator at the Grant Museum of Zoology

Mia Ridge

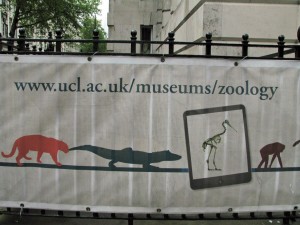

As you approach University College London’s Grant Museum of Zoology through the streets of Bloomsbury, the first hint that there is something unusual inside the stately Rockefeller Building appears in the banners celebrating its re-opening. The line of silhouetted animals is punctuated with the occasional outline of an iPad, the “screen” revealing the skeleton of an animal and hinting at the role of iPads in the museum experience.

Building on the long history of “have your say” interactives in museums, the QRator project was designed to solicit content from the public, museum staff, and academics to “enhance museum interpretation, community engagement and establish new connections to museum exhibit content.”

QRator is a collaboration between a number of departments within University College London (UCL), including the UCL Centre for Digital Humanities, UCL Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis, and UCL Museums and Collections, with funding from UCL’s Beacons for Public Engagement programme. It incorporates technology developed by the Tales of Things project, which is part of a wider Digital Economy Research Councils UK funded research project, Tales of Things and Electronic Memory, organized by UCL along with Brunel University, Edinburgh College of Art, University of Dundee, and the University of Salford.

The QRator project has placed ten iPads in the museum. Each iPad poses a different question about the collections, such as “Should we clone extinct animals?” or “Can we lie about what a specimen is or where it came from?” The questions are linked to particular displays, but the issues raised are relevant to the whole museum. Audiences can also comment online at QRator.org, via the iPhone and Android “Tales of Things” apps or by tweeting with the “#GrantQR” hashtag. Comments left via the iPads, the Tales of Things app, and QRator.org are immediately visible across all three interfaces. The QRator.org and talesofthings.com sites host an archive of questions and comments no longer available on the museum iPads.

The project is well integrated with other signage and calls to “get involved with the museum” in the venue. It is still rare to see digital projects so well integrated with printed material in the museum, and it suggests both an encouragingly audience-centred interpretive focus and the importance of the QRator project for the museum.

The gallery rooms are charmingly Victorian, but the interpretation is very contemporary. The Grant Museum’s self-description as “a centre for discussion and dialogue” is reflected by wall labels that pose questions in addition to providing information. Some displays of extinct species such as the dodo or the quagga have been playfully illustrated with plastic toys or models of the creature.

There is so much on display in the museum that the iPads, first visible as a gentle glow in corners of the gallery, do not dominate the gallery experience. Up close, the iPads cycle through different screens showing the current questions being asked; the responses of previous visitors to the same question; tweets tagged with “#GrantQR”; and a screen with a giant QR code. A QR code is a square barcode that looks a bit like an empty crossword. The squares can be decoded into text, such as a URL, by many mobile phones. Both museums and marketers love QR codes for the ability to link an object or place with online content or interactions, though the extent to which they are understood and used by audiences is still debated.

The links in the QR codes on the iPads take you to the Tales of Things site page for the ‘current question’ displayed on that iPad. The ability to comment directly through the iPad almost seemed to make the QR screen redundant because commenting via the iPad is easier and more immediate.

I found the Twitter screen the least interesting because the tweets shown were about the project itself rather than the questions posed on the iPad, but it did demonstrate that the @GrantMuseum Twitter account was actively finding and sharing interesting visitor comments. By giving comments a life beyond the iPads it created a greater sense of purpose than the usual “have your say” interactive.

The experience was not as conversational as I expected from the initial project publicity. You are not able to comment on other visitor comments (though it took a statement like “EVOLUTION IS A LIE” to make me want to), and only after searching QRator.org later did I find one or two responses from museum staff among the visitor comments. It has been over a year since the museum re-opened so there may have been more resources or interest from staff when it first launched. Questions such as “Do you find skeletons, taxidermy or specimens in fluid more interesting?” have clear potential to fulfill the promise of influencing future displays in the museum but without more responses from staff it is difficult to know what impact visitor comments might have on the museum.

Like many museum projects, the focus of visitor interactions with QRator seems to have shifted during implementation, moving away from a purely object-centric interaction to more general questions based on the functionality of the Tales of Things platform. Given the specialist nature of the collections, it is a better experience for the general visitor for focusing on questions raised by the collections as a whole. While I did not find any of the comments from other visitors particularly illuminating, it is always nice to be asked for your opinion and the questions are chosen so that they can be answered by an engaged visitor without any expertise in zoology.

Overall, the QRator experience is well-integrated with the playful, approachable tone of the rest of the museum. The occasional moderation of comments might help to improve the quality of public contributions to the project, but with the right prompts some visitors will leave thoughtful and insightful comments. The QRator project provides a useful reminder for other museums that visitors will take advantage of opportunities to comment, particularly on accessible platforms like the iPad, and that it is viable for “have your say” interactives to apply a post-moderation model for comments contributed by the public.